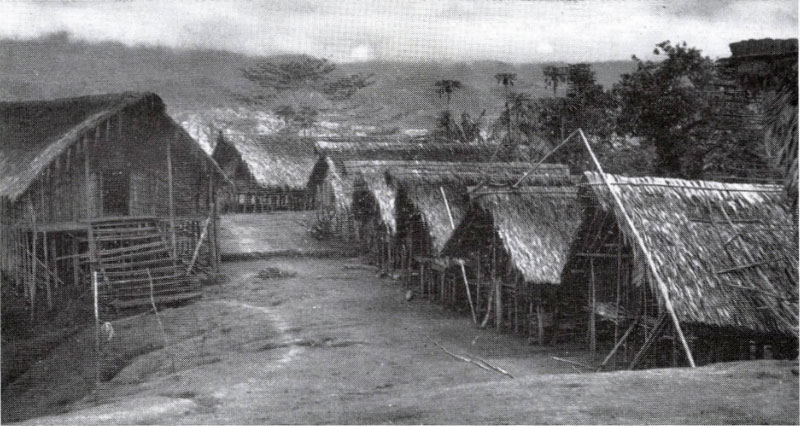

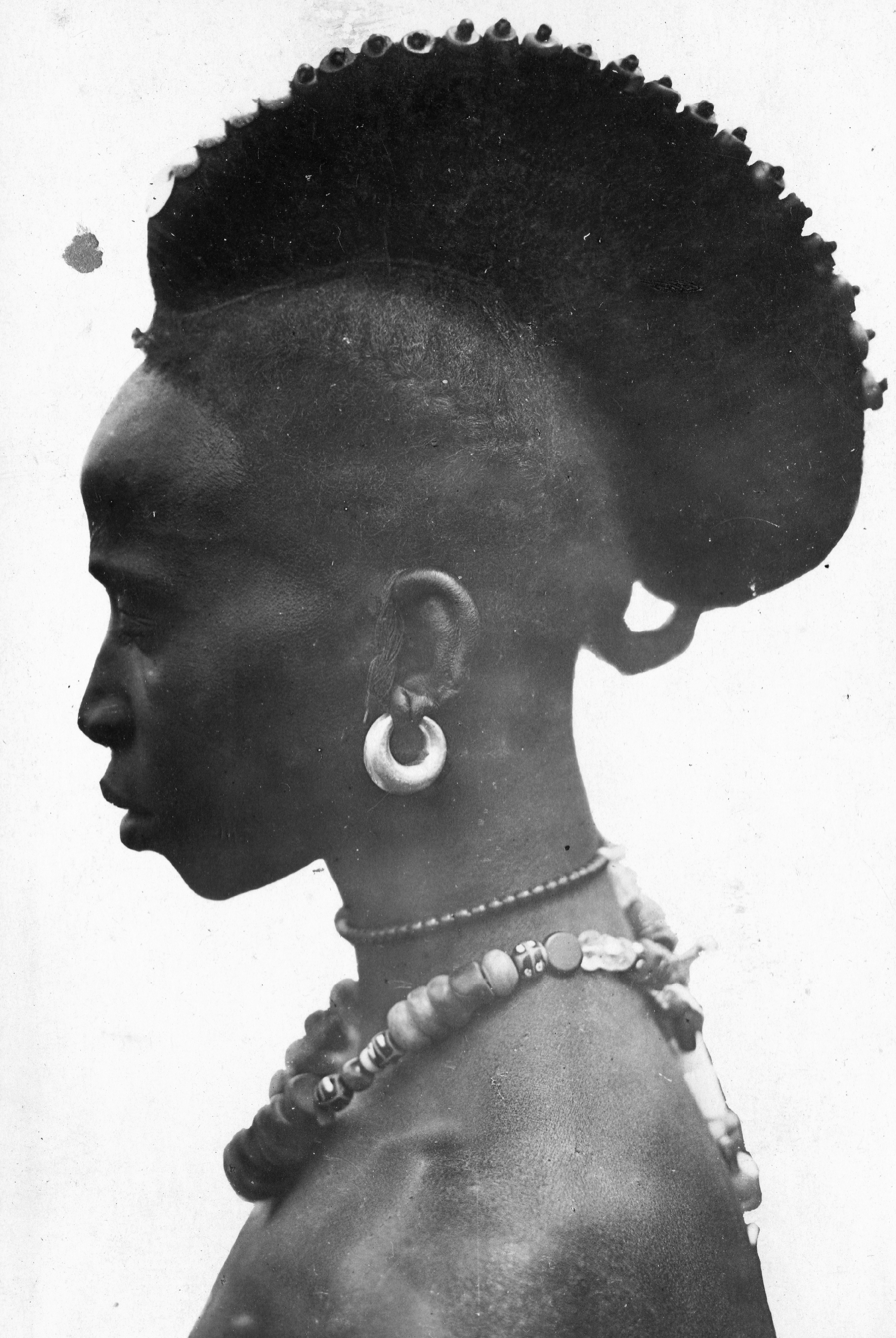

A Papuan village near Kutubu Lake

“Few people know that in the heroic period of discovering Papua New Guinea — apart from Hungarian missionaries — many Hungarian doctors also resided on the island, more concretely on its east side under the governance of Australia. […] During the Second World War, amongst the many fleeing to the West were hundreds of Hungarian doctors. Unfortunately, they could not attain medical jobs, because most countries did not accept their degrees. This was the situation in Australia, where Hungarian doctors could at best work as hospital carers or assistants. But a special situation emerged in the Australian side of Papua New Guinea. During the Pacific war the Japanese occupied the whole area, and the Europeans fled, together with them all doctors. After the war only very few were venturesome enough to return to the dauntingly miserable conditions, therefore on the 462.000 square kilometers area of Papua New Guinea the 2,5 million indigenous inhabitants were left without any reasonable medical care. In the end of the 1940s, Australian authorities decided to permit refugee doctors from Hungary and other foreign countries to professional activities in New Guinea. […] Altogether 15 Hungarian doctors went to New Guinea in the early 1950s. Not all of them could accustom themselves to the harsh conditions, and after a shorter or longer period these returned to Australia. However, 7 of them committed themselves to the sacrificing mission and the majority spent 20–22 years amongst the Papuans.” (Kászoni 1990: 58, 61)

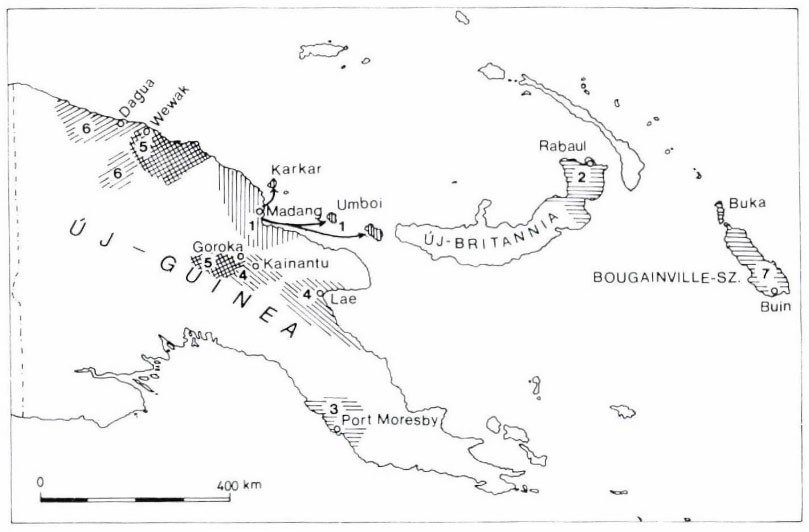

The working districts of Hungarian doctors: 1. Dr. András Becker; 2. Dr. Károly Haszler; 3. Dr. János Loschdorfer; 4. Dr. Károly Mészáros; 5. Dr. Lajos Róth; 6. Dr. Alajos Szymicsek; 7. Dr. Ferenc Tuza.

The working districts of Hungarian doctors: 1. Dr. András Becker; 2. Dr. Károly Haszler; 3. Dr. János Loschdorfer; 4. Dr. Károly Mészáros; 5. Dr. Lajos Róth; 6. Dr. Alajos Szymicsek; 7. Dr. Ferenc Tuza.

Seminar Room

Seminar Room