My latest plan is to send two abstracts to the 17th International Conference of Historical Geographers in Warsaw, July 15-20 and one – the latter abstract here provided – to the Association of American Geographers Annual Meeting in New Orleans, April 10-14 in 2018. In the first case, the first abstract will hopefully be part of the following session:

– SESSION –

Global Histories of Geography 1930–1990

Convenors: Ruth Craggs (King’s College London) and Hannah Neate (Manchester Metropolitan University)

Reflecting on the key centres associated with the emergence of geography as a spatial science in the 1960s Barnes (2002, 508) remarked: “Why are places in Africa not on there, or Asia, or Australasia?” thereby highlighting significant gaps in disciplinary histories and accounts of geography’s development in the second half of the twentieth century. By way of response, this session aims to highlight work into the ‘global’ histories of geography in the period 1930-1990, a period marked by geopolitical transitions including WWII, decolonization and the end of the Cold War. We are looking to make links with scholars who are carrying out research on the history and practice of geography, specifically in submissions that explore scholarly communities of geographers whose contribution to the development of geography in the twentieth century often goes unrecognised in the ‘canon’ of geographical research.

Possible themes for papers:

- Papers focusing on geographers from the global South, Indigenous geographers in settler states, Asian geographies and geographers, geographers from the former Eastern Block

- Biographies of individuals or groupings of geographers

- Accounts that highlight how geography was being pursued in other ‘centres’

- The role and development of national and international disciplinary associations and networks

- Geographical knowledge, expertise and intersections with decolonization and the end of the Cold War

– ABSTRACTS –

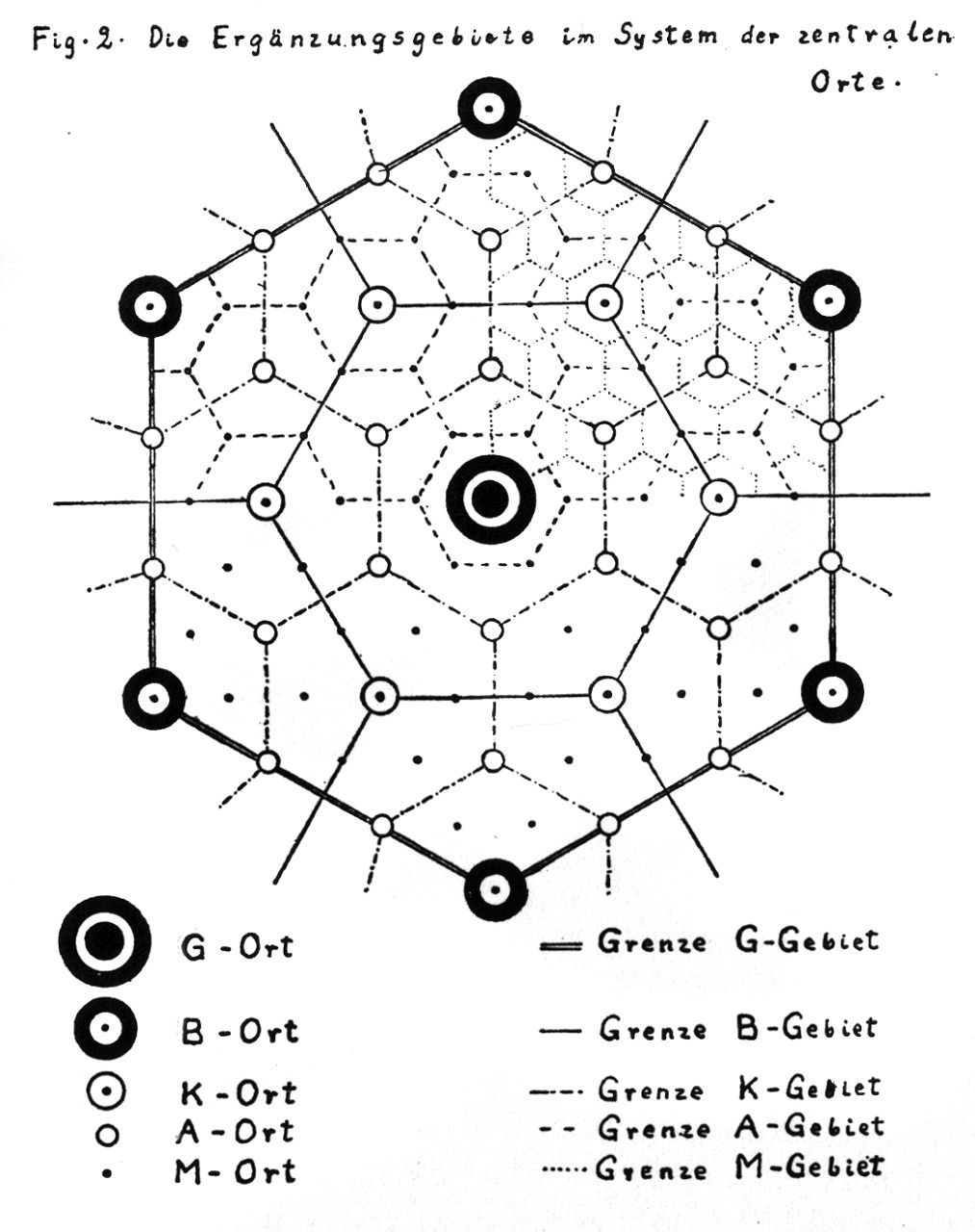

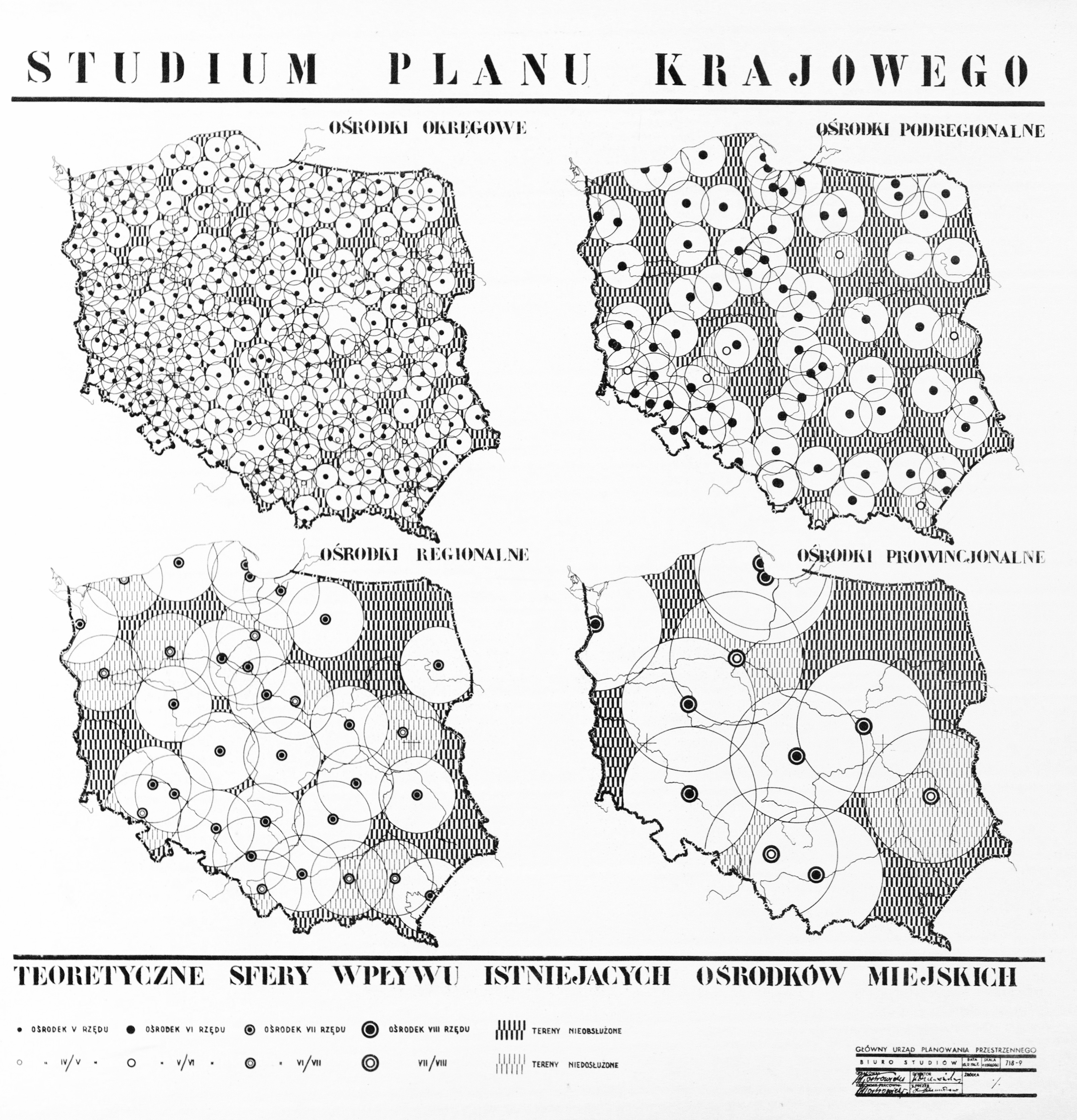

Historical geographies of the “quantitative revolution”: Towards a transnational history of central place theory

Geography’s “quantitative revolution” has been a true textbook chronicle in the discipline’s canonical history. However, historical research has only recently seriously begun to unravel the geographical contexts of its emergence, which is complicated by the simplified narratives that emerged in critical revisionism from the 1970s. This paper offers an interpretative framework from the perspective of the historical geographies of scientific knowledge (HGSK), by focusing on Christaller’s central place theory (CPT) to deconstruct the common Anglo-American narrative, arguing that it has concealed other contexts in the “Second” and “Third” worlds. Early applications (especially in Germany, Poland, Netherlands, Israel) and the wider European discourse of “central places” call for a reevaluation of the canonized narratives of CPT. The globalization of CPT is interpreted through the rising American hegemony in the early Cold War era, which led to the Americanization of German location theories in modernization theory discourse. Networks behind the American, British and Canadian centres show the importance of European locations, such as the Swedish hub in Lund, and the “planning laboratories” of Asian, South American and African contexts after decolonization. Soviet and Eastern Bloc reformism and the institutionalization of regional planning from the late 1950s summoned CPT in the service of centralized state planning, and ignited debates of adaptability between “socialist” and “capitalist” contexts. By reflecting on some of these cases, this paper argues for a transnational history of CPT by readdressing issues of narrativity and historical periodization, and shows the need for provincializing and decolonizing dominant Anglo-American geographical knowledge production.

“The Ghana job”: Opening Hungary to the developing world

Based on interviews, archival and media sources, this paper looks at how post-WWII socialist Hungary developed foreign economic relations with decolonized countries, by focusing on the emergence of Hungarian development and area studies and development advocacy expertise towards developing countries. The paper’s case study is the Centre for Afro-Asian Research (CAAR) founded at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1963 – from 1973 the Institute for World Economy (IWE) – parallel to similar institutions founded in the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc states. CAAR was established as a government think tank by József Bognár, a close friend to Prime Minister János Kádár and perhaps one of the most important figures in socialist era Hungarian reform economics and foreign policy-making. The institute rose as a consequence of the “Ghana job”: Hungarian economists led by Bognár developed the First Seven-Year Plan of Ghana in 1962. The associates of CAAR and IWE promoted export-oriented growth against import-substitution industrialization and summoned geographical development concepts such as “poorly developed countries”, “dependency”, “semiperiphery”, “open economies”, or “small countries” as alternatives to the Cold War categories of “capitalist” and “socialist” world systems. This shift in geographical knowledge production is connected to the geopolitical contexts of the Sino-Soviet split, the Khrushchevian “opening up” of foreign relations, the emergence of the “Third World”, and also the 1956 revolution in the case of Hungary. The role of Ghana and the Eastern Bloc is connected to the 1960s wave of transnational development consultancy and strategies of “socialist globalization”.