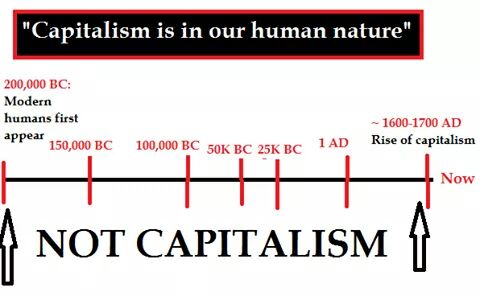

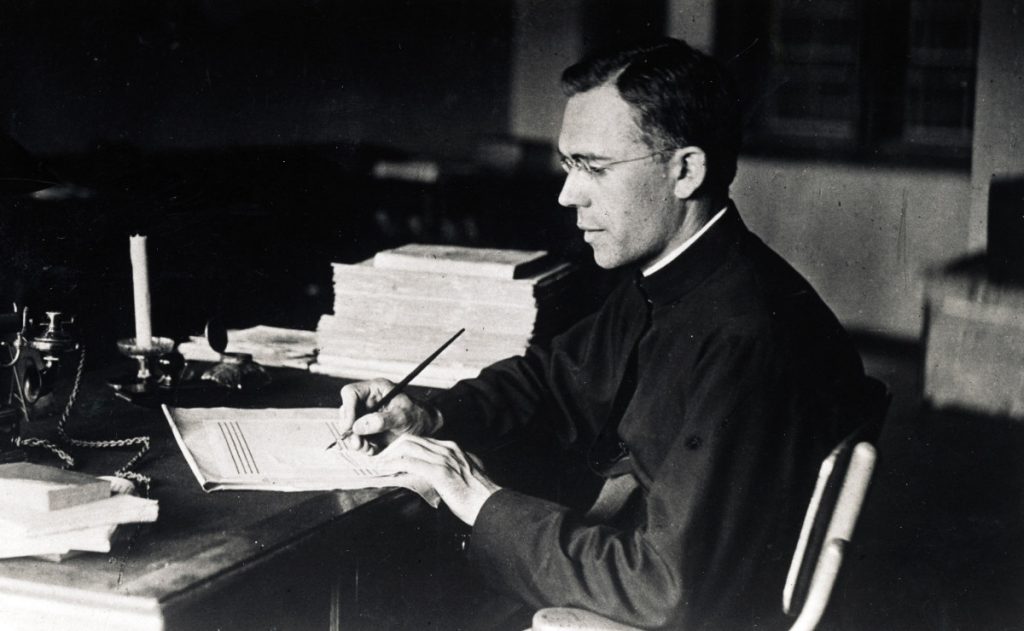

This paper explores the trajectories of the Hungarian Jesuit missionary Béla Bangha (1880–1940) and his priest compatriot, Zoltán Nyisztor (1893–1979) in constructing a distinctively semiperipheral strategy of positioning post-Trianon (1920) Hungary in a global colonial vision connected to postcolonial Latin America. This analysis looks at their various writings, including Bangha’s articles and South American travelogue (1934), and Nyisztor’s papers, autobiographies and travel memoirs (1969; 1971; 1973; 1975; 1978) written in emigration. In interwar Hungary, they were both important leaders of the Catholic revitalization movement and their „militant Catholicism” held staunchly racist, anti-Bolshevik and anti-Semitic views (Nyisztor followed Ferenc Szálasi’s national-socialist, pro-Nazi Nyilas Movement). After 1920, the Trianon trauma of loosing Hungarian imperial hegemony and 2/3 of territory led to various repositioning strategies; Bangha and Nyisztor as travelling intellectuals opened up global arguments from the non-European world. In his South American travelogue (1934), Bangha fantasized about open and spiritually fertile (post)colonial spaces in Latin America, positioning the Hungarian Jesuit heritage of Indian reductions in the 17th century as ideal foundations for national revitalization, racial brotherhood and missionary expansion. This was posed against the colonial-imperialist, racially perilous Protestant mode of spiritless North American (Western) modern capitalism, thereby countering the dominant Western/Atlantic/Protestant narrative of global colonial history by channelling Hungarian ambitions into emancipating the silenced Southern colonial history. Bangha and Nyisztor developed racial visions of a decadent Indian race, which could only be saved by a white influx of racial mixing and Catholic civilizing, supported by an organized local Hungarian colonist diaspora – consisting in part of post-Trianon emigrants – through missionary activity. This paper aims to show their inherent semiperipheral dynamics of positioning Hungary in-between the global centre and periphery via a global colonial discourse connecting racial ideas from the non-European post-colonies with local Hungarian discussions of racial struggle and white supremacy.

Keywords: semiperipheral post/coloniality, white race, global colonial history, Hungarian Catholicism, Latin America

© Copyright – Content is protected by copyright!

Citation:

Ginelli Z. (2019): The Semiperipheral Colonial Alternative: Visions of Hungarian Catholic Postcoloniality in Latin America. Critical Geographies Blog. 2019.07.11. Link: /2019/07/11/the-semiperipheral-colonial-alternative-visions-of-hungarian-catholic-postcoloniality-in-latin-america