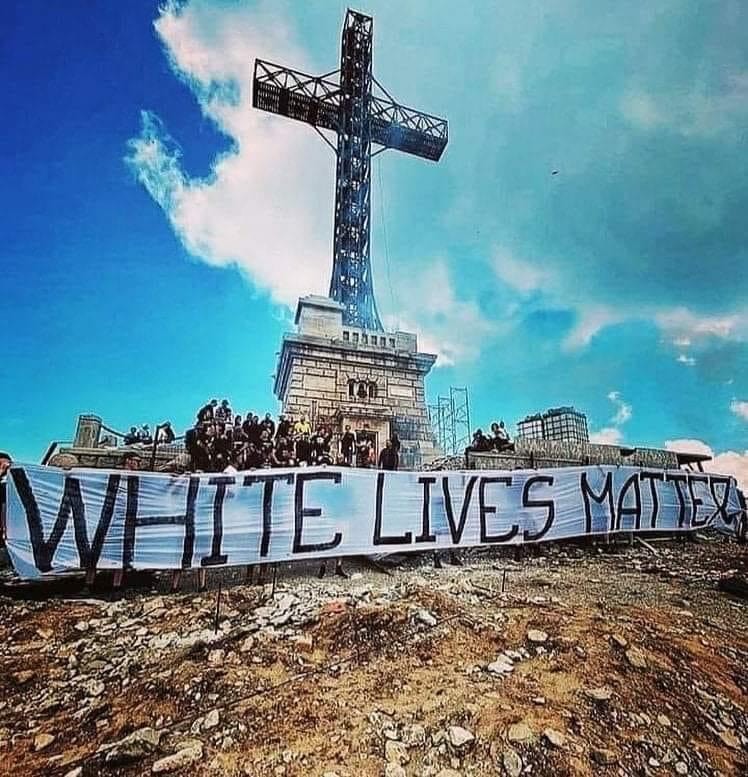

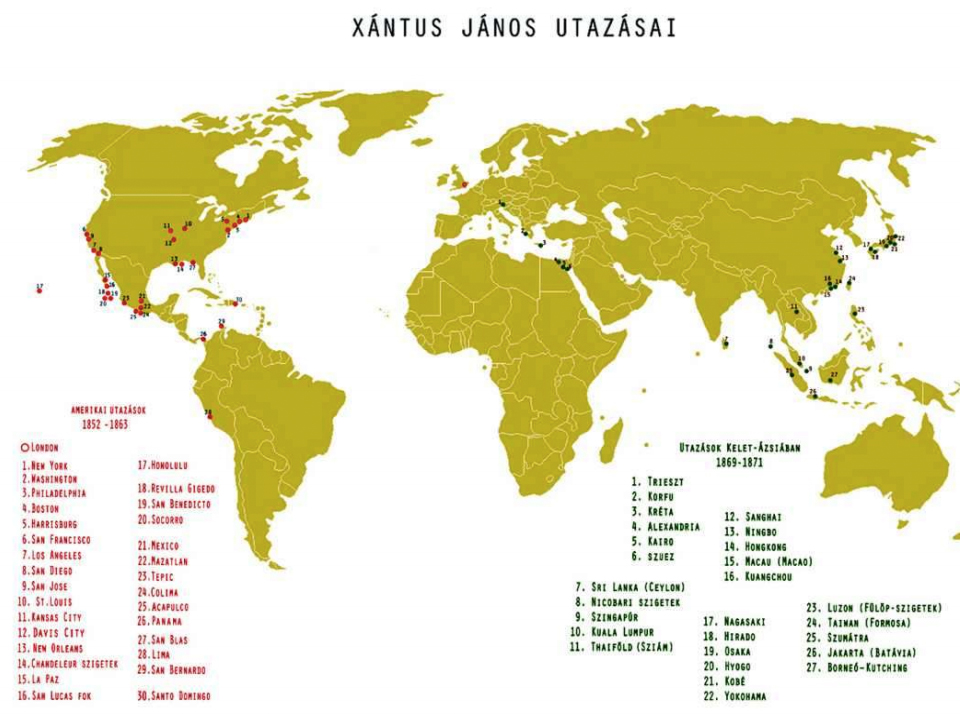

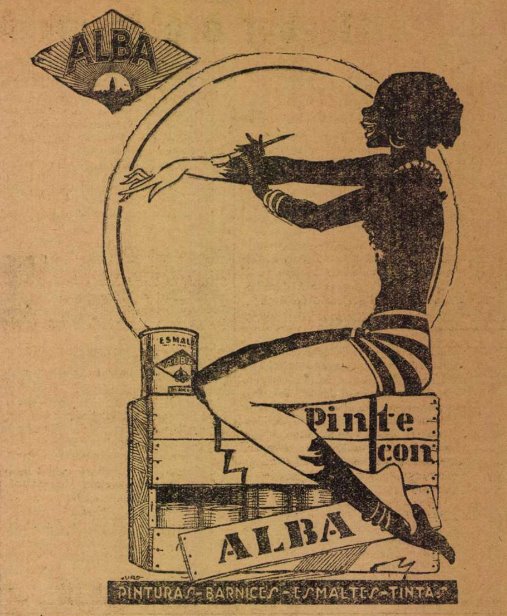

The perhaps much overlooked geographical significance of recent social unrest in the USA related to the Black Lives Matter and various anti-racist and decolonial movements is how quickly they ’scaled up’ globally, sparking sharp debates in Eastern Europe for the first time. Although in the region these movements have been most often dismissed either as an ideological threat or simply irrelevant, still the discussions of colonial and racial memory politics have provoked intriguing questions about comparability. Since the 2010s, authoritarian right-wing regimes of populist nationalisms have constructed an imaginary dividing line between “former colonizer” Western and “non-colonizer” Eastern European countries, expressing fears of becoming Western “colonies” whilst victimizing their ‘peripheral whiteness’ in an identity politics of recognition. Stuck in an uncomfortable ’in-between’ position within global colonialism, Eastern Europeans have historically embraced colonial Europeanness and whiteness whilst excusing from its dark moral burden – ultimately producing contradictory silences in the region’s complicated racial and colonial history. How can we understand this semiperipheral Eastern European relation to global colonialism and racism? How can decolonialism, seemingly relevant only to the imperialist West and the postcolonial Global South, be also relevant to a region which is commonly known as “non-colonizer” and without colonial history? This paper aims to unpack Eastern European ‘frustrated whiteness’ through exploring a decolonial approach to this uneasy and contradictory semiperipheral position in global (post)colonialism.

CULTURE AT A CROSSROAD: WHAT COLLABORATION DO WE WANT IN EASTERN EUROPE?

Friday, September 18th, 2020

12.00 pm – 4.30 pm

Facebook event and live stream

East European Biennale Alliance (EEBA) presents ‘Culture at Crossroads: What Collaboration Do We Want in Eastern Europe?’ – an online symposium which will be streaming on Friday September 18th 2020 from 12 pm (CET). The symposium will be held in English and is organised by the founding members of EEBA – Biennale Warszawa, Bienále Ve věci umění / Matter of Art Praha, OFF-Biennále Budapest a Kyiv Biennial (VCRC).

Participants:

Tereza Stejskalová, Veronika Janatková, Dominika Trapp, Kateřina Smejkalová, Noemi Purkrábková, Zoltán Ginelli, Eszter Lázár, Eszter Szakács, Serge Klymko, Wolfgang Schwärzler, Vasyl Cherepanyn, Aleksandra Jach, Michał Dąbrowski, Bartek Frąckowiak, Marta Michalak

What should we expect from art and art institutions in the next few years or decades? What is their role at a time of a major social transformation? Why do we make or present art, for whom, and does it make sense to continue using the same formats and materials as before? What should art be focusing on and what difference can it make? These are old questions but they need to be asked whenever conditions are changing—and they are changing now, drastically. Without a doubt, the current situation leads us to rethink and reimagine the way art institutions, art practices, and artists operate. We ask these questions from a perspective of artists and curators who operate in the Eastern European region—the periphery of Europe. As we have witnessed again during the COVID-19 pandemic, the interconnected global challenges take specific shape in our region. How are we, the art/cultural sector (institutions, curators, critics, artists, producers) preparing ourselves to operate in the future? How should we rethink the ways of creation, production, and distribution of artworks, projects, and events?

Perhaps, as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the art world will become smaller, more local, more grounded in local communities. This can be a good thing in terms of the sustainability of both: the human and non-human lives on this planet. After all, the opportunities for artistic and curatorial mobility have never been distributed equally or justly. But the notion of local can also be a trap. Under the rule of conservative governments in our countries, critical art, critical artists and critical art institutions have become extremely precarious, in some cases even directly persecuted. International connections are a crucial resource of not only intellectual exchange and finances but also of moral and political support. In what forms, formats, and mediums will this international cooperation be able to continue? How can we share gestures of solidarity with our Eastern European collaborators, partners, friends, comrades in struggle?

The newly established East Europe Biennial Alliance, comprised of the Biennale Matter of Art in Prague, Biennale Warszawa, Kyiv Biennial, and OFF-Biennale Budapest, aims to propose a different narrative of the East European region and redefining the way cultural institutions collaborate. As contemporary biennials have become an important vehicle reaching new contexts and audiences, the Alliance is designed to enhance the role of biennials in shaping innovative forms of international solidarity, expanding socio-political imagination and elaborating alternative cultural solutions. The Alliance brings biennials together to develop a shared vision and regional collaboration producing cross-border meetings, public events and working on the common agenda for upcoming years.

—

Program

I. TECHNOLOGIES AND THE WORK OF COLLABORATION

12:00-12:10 Tereza Stejskalová & Veronika Janatková: Introduction

12:10-12:25 Kateřina Smejkalová: Action and Interaction in Digital Capitalism

12:25-12:40 Noemi Purkrábková: Crossing the Distance: Hopes & Sorrows of Art and Music in the Virtual Sphere

12:40-12:50 Discussion

12:50-13:00 Break

II. DECOLONIZATION AND/OF COLLABORATION

13:00-13:15 Zoltán Ginelli: Decolonizing the Non-Colonizers? Eastern Europe in Global Colonialism and Semiperipheral Decolonialism

13:15-13:30 Eszter Lázár & Eszter Szakács: Practices of Alliance Building

13:30-13:45 Dominika Trapp: Peasants in Atmosphere

13:45-14:00 Discussion

14:00- 14:30 Lunch

III. ECOLOGIES AND VISUAL POLITICS OF COLLABORATION

14:30-14:45 Aleksandra Jach & Michał Dąbrowski: How to Talk about the Climate Crisis?

14:45-15:00 Wolfgang Schwärzler: Building the East Europe Biennial Alliance’s Graphic Design.

15:15-15:30 Vasyl Cherepanyn & Serhiy Klymko: Political in Content, Visual in Form: Notes on Cultural Internationalism.

15:30-15:45 Bartek Frąckowiak & Marta Michalak: Eastern Europe: Three Scenarios for the Future of Transnational Collaboration in the Cultural Field

15:45-16:15 Discussion

© Zoltán Ginelli

Ginelli Z. (2020): Decolonizing the Non-Colonizers? Eastern Europe in Global Colonialism and Semiperipheral Decolonialism Critical Geographies Blog, 2020.07.03. Link: /2020/07/03/decolonizing-the-non-colonizers

n’s racism in his The American Empire (2004), but I could find only some littered personal accounts on the racism of other important geographers, like Carl Ortwin Sauer (this calls for another post). There aren’t even traces of reflection on these issues in any of the most prominent accounts on the history of American geography, like in David Livingstone’s The Geographical Tradition (1992), Ron J. Johnston’s (and James D. Sidaway’s) Geography and Geographers (2015), Richard Peet’s Modern Geographical Thought (1998), Geoffrey J. Martin’s American Geography and Geographers (2015) or his All Possible Worlds (2005), just to name a few, and nor in Reflections on Richard Hartshorne’s Nature of Geography (1989).

n’s racism in his The American Empire (2004), but I could find only some littered personal accounts on the racism of other important geographers, like Carl Ortwin Sauer (this calls for another post). There aren’t even traces of reflection on these issues in any of the most prominent accounts on the history of American geography, like in David Livingstone’s The Geographical Tradition (1992), Ron J. Johnston’s (and James D. Sidaway’s) Geography and Geographers (2015), Richard Peet’s Modern Geographical Thought (1998), Geoffrey J. Martin’s American Geography and Geographers (2015) or his All Possible Worlds (2005), just to name a few, and nor in Reflections on Richard Hartshorne’s Nature of Geography (1989).