Call for Papers | American Association of Geographers Annual Meeting | Seattle, WA | April 7–11, 2021 | Virtual Session

Convened by Zoltán Ginelli and Jonathan McCombs

What would it mean to ‘decolonize’ Eastern Europe? Recent debates and political struggles around anti-racism and decolonization in the West have spawned reactions of ‘Eastern European exceptionalism’ within the colonial project and the contemporary global racial order. In a region perceived as “never having colonies,” the discourse of colonialism has recently been reimagined on a dividing line along the former Iron Curtain separating ‘colonizer’ and ‘non-colonizer’ countries within Europe. Yet, this discourse, which reaches back to the socialist era and beyond, obscures the role Eastern European countries’ played in both colonial and anti-colonial movements, and downplays their material and ideological interests in the global colonial system. This intriguing geography of converging postsocialist and postcolonialist histories inspires us to question why there is so little discussion about the region’s complex historical relations to global colonialism. We aim to answer by situating Eastern Europe within broader colonial, anti-colonial and decolonial projects, to understand how the region’s historically and geographically shifting relations to coloniality and race inform current political dynamics.

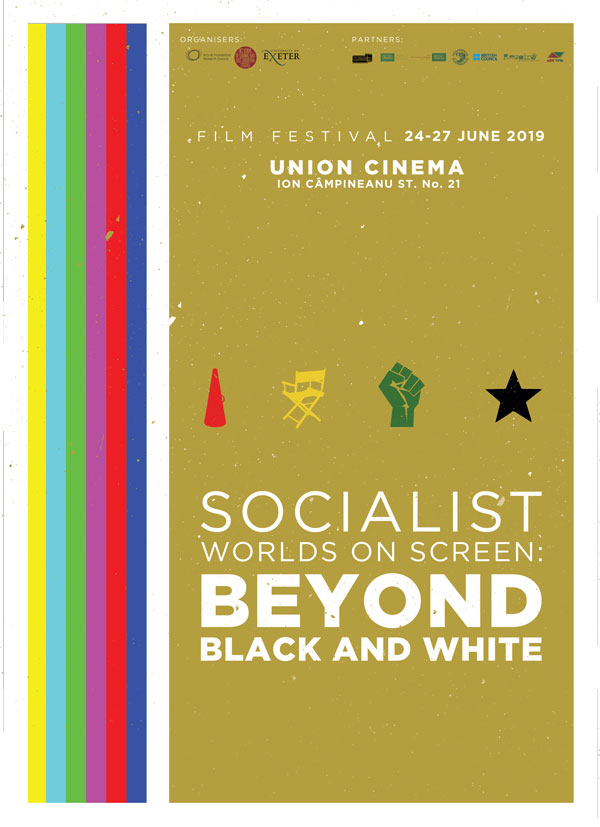

The specific role of Eastern Europe within global capitalism has been conceptualized by an important strand of critical research as occupying a persistent ‘in-between’ or semi-peripheral position within the capitalist world-system (Wallerstein 2004, Böröcz 2009, Boatcă 2010). This longue durée structural continuity of Eastern Europe, despite shifting state formations and governmental logics, forces researchers to grapple with a complex history of often antagonistic roles the region played within capitalist colonialism and racial hierarchies globally (Wimmler and Weber 2020). However, the region is seldom discussed within the global history of colonialism, despite its significant contributions in knowledge, material resources, and peoples to various global colonial ambitions, imperialist trajectories and racial (geo)politics (Mark and Slobodian 2018, Grzechnik 2019, Ginelli forthcoming). The advent of post-WWII Afro-Asian decolonization, the Non-Aligned Movement and socialist internationalism reconfigured previous colonial relations of Eastern Europe. State-socialist Eastern Bloc governments tried to leverage their relatively privileged semiperipheral positions to both aid and exploit Third World decolonization movements, and to both advance and alleviate Soviet influence in the global Cold War (Ginelli 2018, Muehlenbeck and Telepneva 2018, Mark, Kalinovsky and Marung 2020). However, despite their anti-colonialist and anti-racist alliances against the West, communists seldom questioned their own Eurocentrism and remained structurally dependent on unequal trade and Western capital.

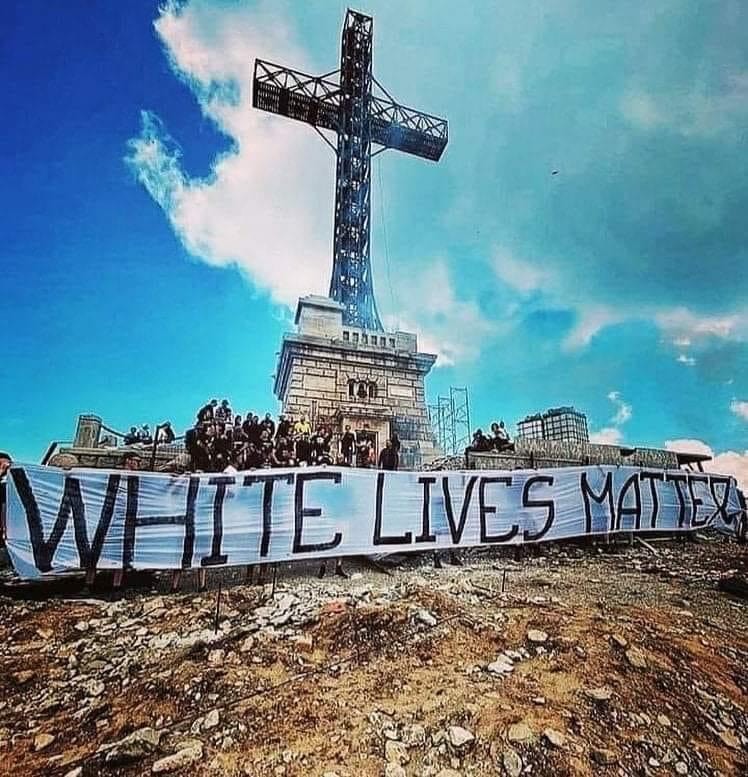

The system change beginning in 1989 inaugurated a ‘return to Europe’ as most Eastern Bloc countries integrated into the European Union and hegemonic, West-led neoliberalism (Mark et al. 2019). This has been conceptualized as a neocolonial relation and ‘Thirdworldization’ (Frank 1994), but also a return to ‘whiteness’ and a turn away from former anti-colonial solidarities with the Third World that started already since the late 1970s. After the 2008 economic crisis, these post- and neocolonial relations provided fertile ground for nationalist political parties to win popular support for a political agenda that pits national interest against EU-led, liberal colonialism-imperialism, whilst increasingly authoritarian Eastern European governments turned towards state-centric capital accumulation and clientelistic neoliberal policies (Szombati 2018, Scheiring 2020). These policies only further entrenched Eastern Europe’s economic dependency on Western capital, while politicians continued to wage a ‘culture war’ against perceived Western multiculturalism and a ‘comprador’ left-liberal opposition. The 2015 refugee crisis reanimated government-supported racist civilizational discourses, bordering, discrimination and anti-immigration policies against the former Third World or the (now) Global South. In addition, the presumed “white innocence” (Wekker 2016) of Eastern Europeans within the larger colonial project have helped sustain austere border protection policies and racialized displacements of Roma (Ivancheva 2015; Picker 2017; Vincze and Zamfir 2019). In this political climate, condemnation from the international community only reinforces anti-globalist colonial sentiments within the political right. The left refuses to embrace a broadly decolonial politics, instead acquiescing to the Eurocentric political consensus, which entails a denial of a colonial present.

In this current context, we believe that exploring progressive ways to decolonize Eastern European knowledge by situating the region’s relations to coloniality and race within global structural contexts is a necessary step towards devising local emancipatory projects and contributing to global discussions about decolonization (Manolova, Kusic, and Lottholz 2019). We set out to grapple with the ‘colonial complexity’ of Eastern Europe’s ‘in-between,’ semi-peripheral position within the global capitalist world-system: being both an object of and facilitator to colonial and racial relations, and being both dependent upon – often still West-governed – (post)colonial networks and purveyor of European colonialism and racism on the global scale. To this end, we seek papers that address the following topics:

- Global histories of the political role and structural integration of Eastern Europe in global colonialism, including the region’s relations to anti-colonialism and decolonization;

- Comparative and relational epistemologies, theories and methods on ‘whiteness,’ race, class, and gender in Eastern Europe from post-, decolonial and global historical perspectives

- Interrelations and circulations between the ‘Second’ and the ‘Third Worlds’ that shaped the everyday lives of local citizens, migrant workers, students, artists, travellers, experts and revolutionaries;

- Re-conceptualizing 1989 and postsocialist change through post- and decolonial perspectives within global historical change, including shifting positions and circulating concepts of coloniality and race;

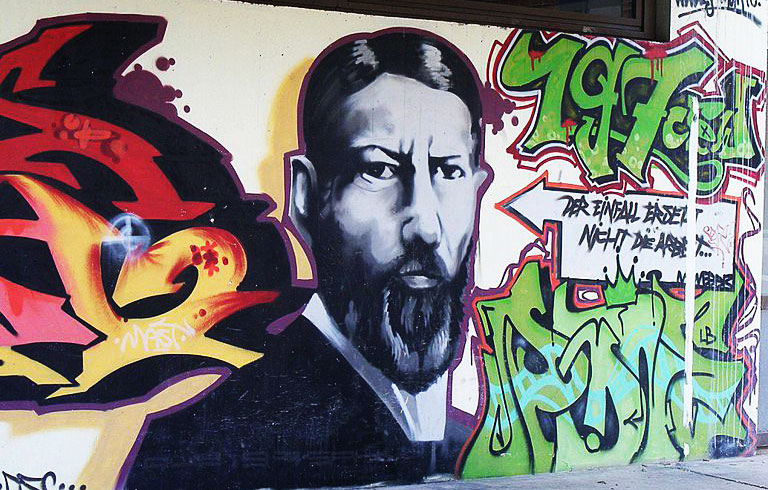

- The recent resurgence of ‘colonial discourse’ and the mobilization of colonial pasts and experiences in Eastern Europe within recent political discourse;

- The role of Eastern Europe in ‘bordering Europe’, ‘Fortress Europe’, and post-2008 civilizational and racial ‘othering’ against the former Third World or the Global South;

- Coloniality in anti-coloniality, continuities and contestations of Eurocentrism, colonialist and racist tropes in Eastern European knowledge and culture from a global historical perspective;

- Placing local and regional colonialisms/imperialisms and racisms in Eastern Europe, including their current political heritage, within global colonialism;

- Recent Eastern European perceptions, interpretations and political mobilization of or resistance against anti-racist and decolonization movements (e.g. Black Lives Matter).

Please email abstract submissions (250 words) to [email protected] and [email protected] by November 10, October 26th, 2020.

Download in .pdf.

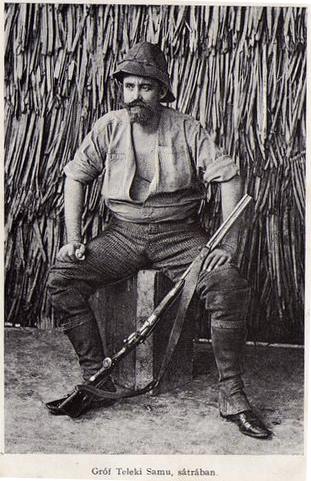

Cover photo: The native American Indian feather headdress displaying the Hungarian national colors of red, white and green was given as a gift by the American scouts to the Jamboree Camp Chief and Chief Scout of Hungary, Count Pál Teleki at the 4th World Scout Jamboree in Gödöllö, Hungary in 1933.

Join our Facebook group Decolonizing Eastern Europe and follow us on Twitter (@DecolonizingE).

References:

Boatcă, M. (2010). “The Eastern Margins of Empire: Coloniality in 19th Century Romania.” In: Mignolo, W. and Escobar, A. (eds.): Globalization and the Decolonial Option. London and New York: Routledge.

Böröcz, J. (2009): The European Union and Global Social Change: A Critical Geopolitical-Economic Analysis. London and New York: Routledge.

Frank, A. G. (1994): The Thirdworldization of Russia and Eastern Europe. In: Hersh, J., Schmidt, J. D. (eds.): The Aftermath of ‘Real Existing Socialism’ in Eastern Europe. Vol. 1: Between Western Europe and East Asia. London: Palgrave Macmillan. 39–61.

Ginelli, Z. (2018): Hungarian Experts in Nkrumah’s Ghana: Decolonization and Semiperipheral Postcoloniality in Socialist Hungary. Mezosfera, 5. http://mezosfera.org/hungarian-experts-in-nkrumahs-ghana

Ginelli, Z. (forthcoming): Global Colonialism and Hungarian Semiperipheral Imperialism in the Balkans. In: Boatcă, M. (ed.) De-Linking, Critical Thought and Radical Politics. London: Routledge.

Grzechnik, M. (2019): The Missing Second World: On Poland and Postcolonial Studies. Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 21(7): 998–1014.

Ivancheva, M. (2015): From Informal to Illegal: Roma Housing in (Post-)Socialist Sofia. Intersections: East European Journal of Society and Politics, 1(4): 38–54.

Mark, J., Iacob, B. C., Rupprecht, T., Spaskovska, L. (2019): 1989: A Global History of Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mark, J., Kalinovsky, A. and Marung, S. (eds.)(2020): Alternative Globalizations: Eastern Europe and the Postcolonial World. Indiana University Press.

Mark, J. and Slobodian, Q. (2018): Eastern Europe in the Global History of Decolonization. In: Thomas, M., Thompson, A. S. (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of the Ends of Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Manolova, P., Kusić, K., Lottholz, P. (2019): Introduction: From Dialogue to Practice: Pathways towards Decoloniality in Southeast Europe. d’Versia Special Issue: Decolonial Theory and Practice in Southeast Europe, (March): 7–30.

Muehlenbeck, P. E. and Telepneva, N. (eds.)(2018): Warsaw Pact Intervention in the Third World: Aid and Influence in the Cold War. I. B. Taurus.

Picker, G. (2017). Racial Cities: Governance and the Segregation of Romani People in Europe. London and New York: Routledge.

Scheiring, G. (2020): The Retreat of Liberal Democracy: Authoritarian Capitalism and the Accumulative State in Hungary. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Szombati, K. (2018): The Revolt of the Provinces: Anti-Gypsyism and Right-Wing Politics in Hungary. New York – London: Berghahn Books.

Vincze, E., and Zamfir, G. (2019): Racialized Housing Unevenness in Cluj-Napoca under Capitalist Redevelopment. City, 23(4–5): 439–460.

Wallerstein, I. (2004). World-Systems Analysis; An Introduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Wekker, G. (2016): White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham: Duke University Press.Wimmler, J., and Weber, K. (eds.) (2020): Globalized Peripheries: Central Europe and the Atlantic World. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Press.