Zoltán Ginelli

Book Plan

The quantitative revolution has been an epochal textbook chapter in geography’s canonical history, marking a time when the discipline transformed into a rigorous social science backed by predictive mathematical methods in the early Cold War. An iconic scientific concept of this quantitative movement, most notably related to Walter Christaller (1933) and August Lösch (1939), was central place theory (CPT), which postulated a triangular-hexagonal structure of hierarchical settlement systems based on marginalist economics and behaviourist assumptions. It was a foundational theory for the emerging field of spatial analysis, including regional science (Isard, 1956) and regional or urban economics. With the intensive globalization of the quantitative revolution after its emergence from the Second World War in the United States (Barnes and Farish 2006), location theories such as CPT became very influential and widespread in urban and regional planning across the entire world. But in the West, vigorous efforts to criticise spatial science from the 1970s onwards (e.g. Gregory, 1978) developed a revisionist narrative that stressed the influence of positivism, rationalism, technocratism, and Cold War American hegemony. This ultimately added to the already reduced view of actual historical events (Livingstone, 1992; cf. Van Meeteren, forthcoming), while recent research has only begun to unravel the variegated geographical contexts of the quantitative revolution (e.g. Barnes, 2003). Reflecting on its initial North American centres, Barnes (2002, 508) passingly remarked: “Why are places in Africa not on there, or Asia, or Australasia?” Following Barnes’s plea for a more wider interpretation, we attempt to pose a number of questions. How did quantitative spatial analysis and planning develop in different parts of the world? In what different geographical contexts were location theories like CPT read, reinterpreted, applied, and mobilized? How were these often very different contexts connected?

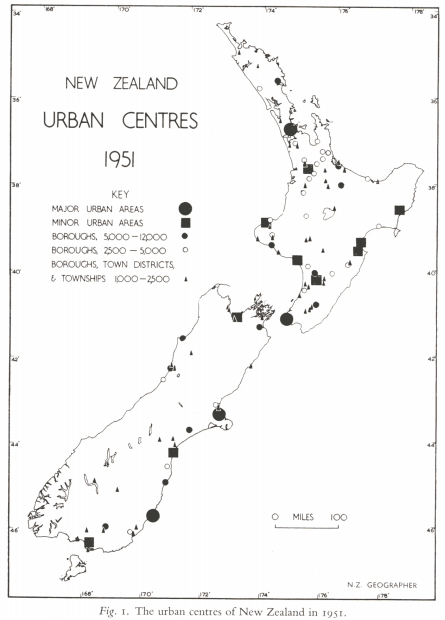

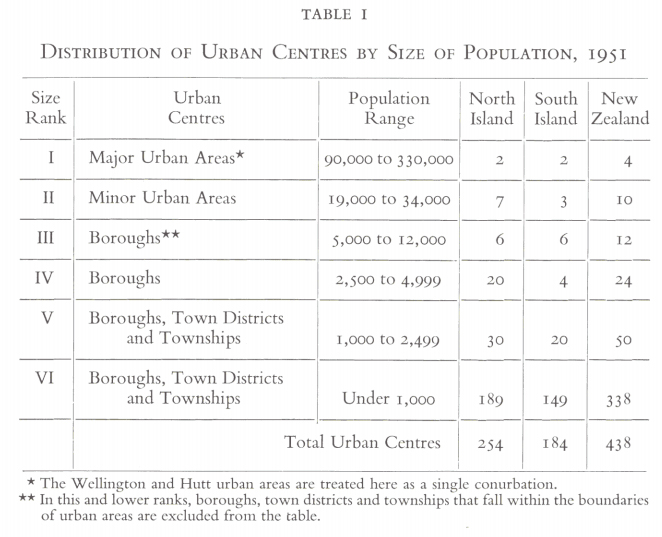

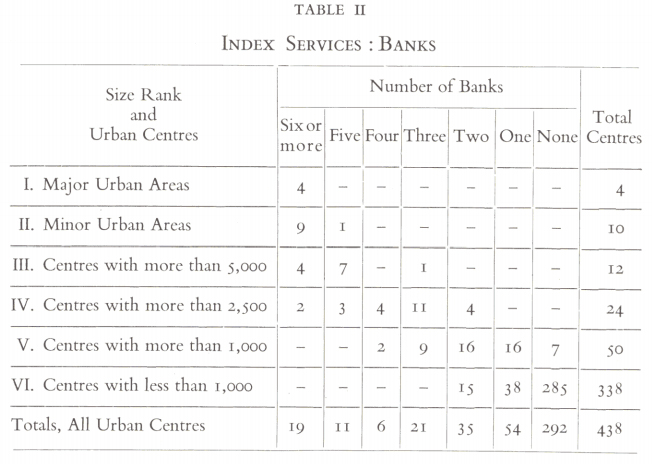

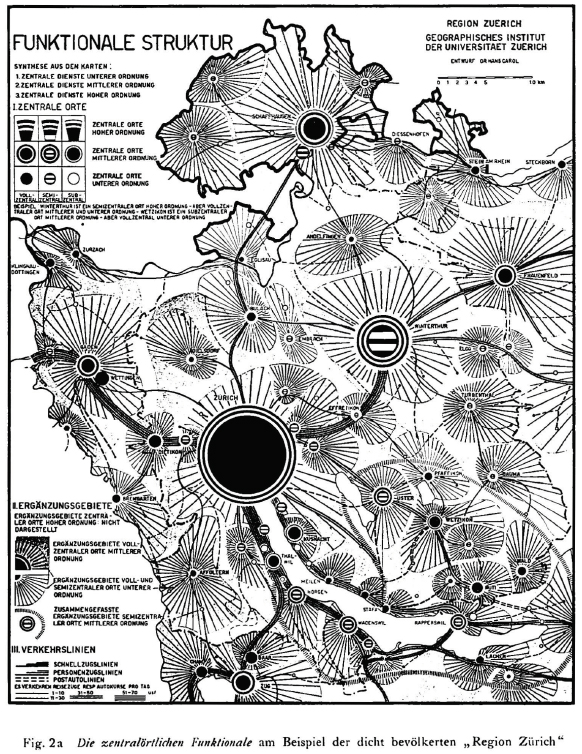

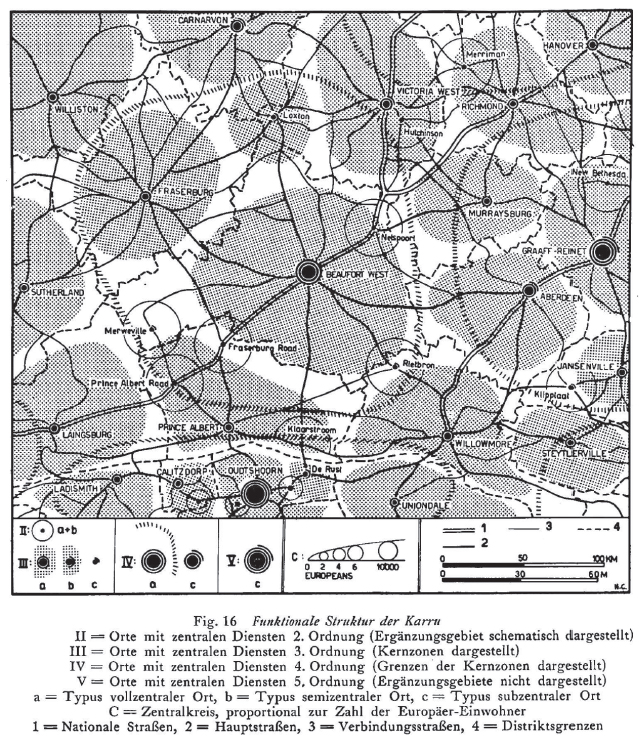

This book offers to fill this significant gap in geography’s twentieth century global history by following a transnational framework based on the historical geographies of scientific knowledge (Livingstone, 2003; Withers, 2007). It aims to deconstruct the mainstream Anglo-American narrative by tracing the quantitative revolution through the circulation and local applications of CPT in the “Second” and “Third” worlds and also into the pre-Cold War era (Ginelli 2018; Ginelli, in preparation). CPT was abstracted and canonized pragmatically by American-led spatial science despite originating from a much wider and more complex European interwar discourse than commonly appreciated (Radeff, 2012; Van Meeteren and Poorthuis, 2018). Antecedents reached into late 18th and 19th century ideas by German, French, and Swiss political economists, engineers, mathematicians, and geographers (Istel, 2002), and the so-called Garden City Movement across Europe (Fehl, 1992). The discussion of location theories grew rapidly in interwar Europe, as the Great Depression (1929–33) and world economic crisis ignited state-led interventionism and technocratism, which was embedded in a transnational discourse of rationalizing reforms by emerging administration science and regional planning, the application of functionalist and modernist ideas, Fordist-Taylorist development, mathematical economics, and long-term planning that disregarded ideological barriers. During the Second World War, CPT was intensively applied by Christaller under the “reactionary modernist” Nazi regime to plan the colonization and German resettlement of Poland by the Third Reich (Generalplan Ost) (e.g. Rössler, 1989; Preston, 2009; Barnes and Minca, 2013). Notable early applications included Estonia (Kant, 1935), the Nordoostpolder settlements in the Netherlands in the 1940s (Bosma 1993), the new settlements of expanding Israel in the mid-1950s (Trezib, 2014), research and application in regional planning in Britain (e.g. Dickinson, 1942; Smailes, 1944), introduction to the USA (Ullman, 1941; Brush, 1953; Berry & Garrison, 1958), and the regional planning of Sweden (e.g. Godlund, 1951). The yet weak American, British, and Canadian network of the quantitative movement was supported by the Swedish hub in Lund, which was also important in disseminating the application of location theories into Scandinavia and other parts of Europe in the 1960s (Barnes and Abrahamsson, 2017; Van Meeteren, in preparation). The Anglo-American impulse traversed easily into other Anglophone contexts such as Australia and New Zealand (e.g. Duncan 1955), and reached France through Canada in Francophone networks (Cuyala, 2015), while it helped legitimize the German reinvigoration of CPT in the 1960s in face of its wartime burden (Kegler, 2015).

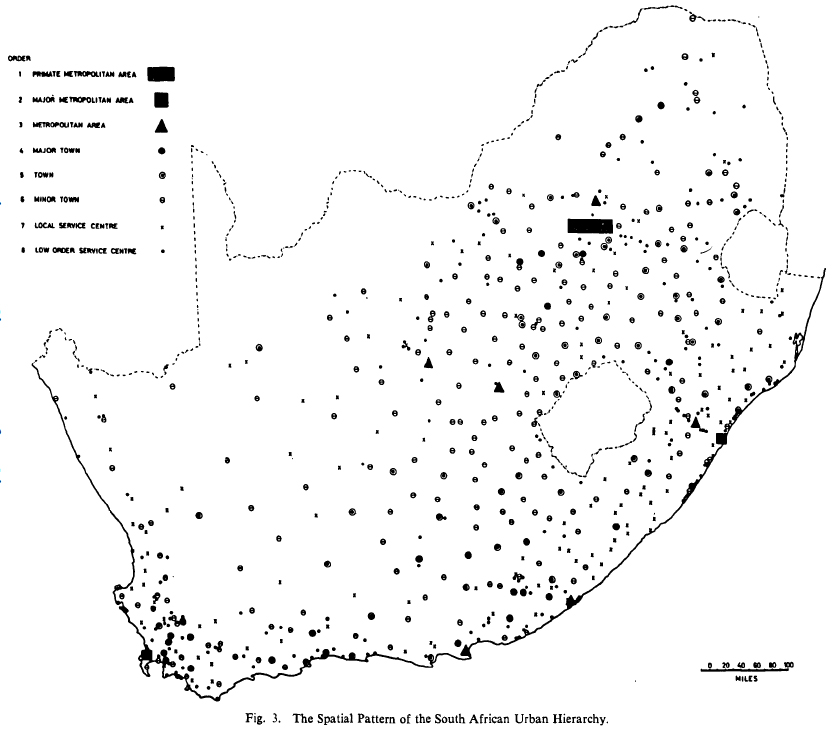

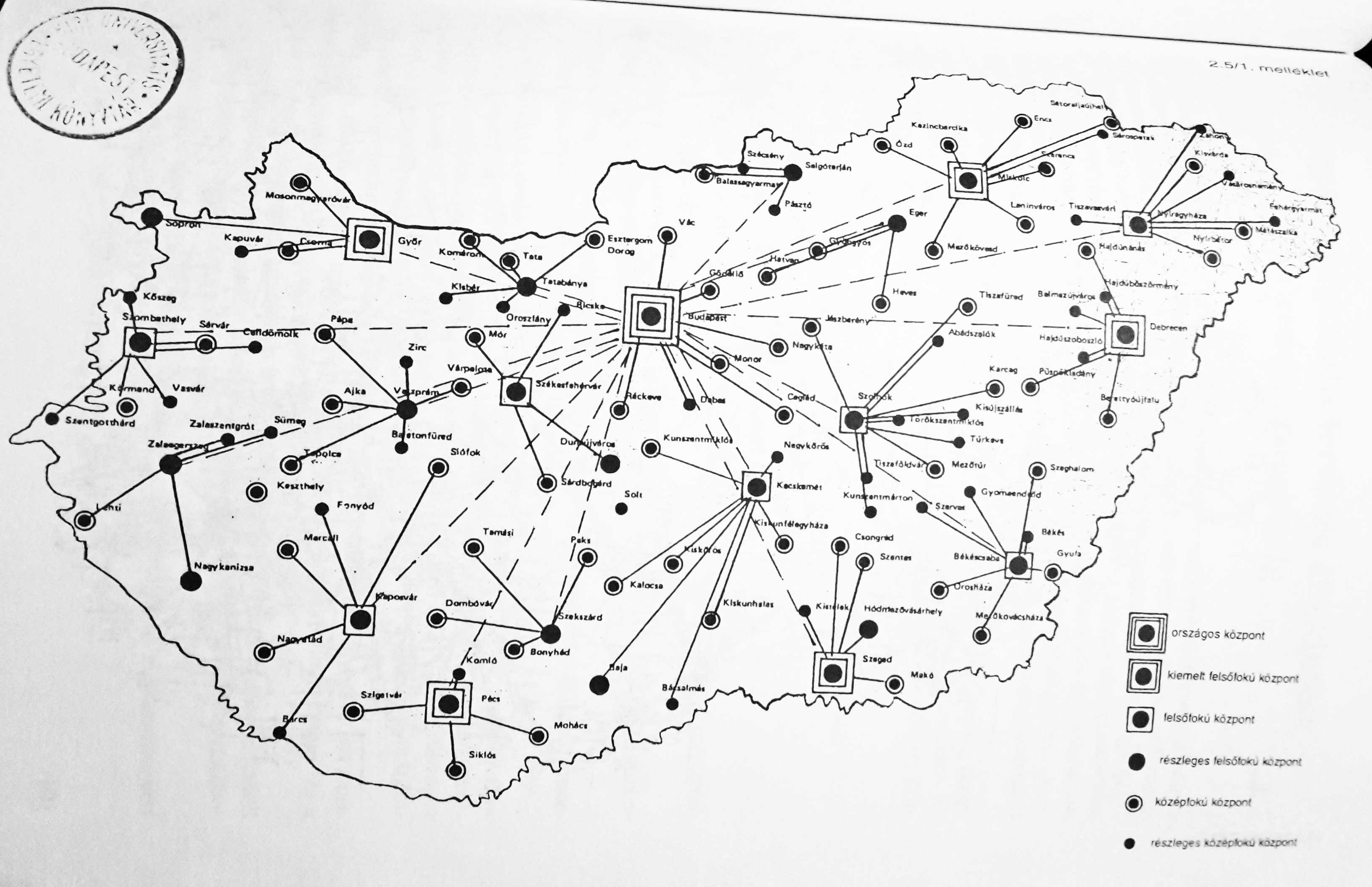

These mostly North Atlantic and Western, Central, and Northern European cases were followed by parallel developments and were increasingly connected into a global network despite Cold War ideological tensions, especially through international organizations such as the International Geographical Union and urban or regional planning organizations. The globalization of CPT under American Cold War hegemony from the early 1960s led to the Americanization of German location theories in an economistic modernization discourse, supported by USAID, United Nations, and World Bank projects. CPT became an important instrument of state-interventionist modernization and urbanization policies in the “planning laboratories” of the Global South, embedded in existing and emerging postcolonial knowledge networks devised by important centres of the quantitative revolution (Ginelli, in preparation). Early applications in India were followed by various others in South East Asia, West Asia (Clark & Costello 1973), and also East Asia (Ullman 1956), such as China (Skinner, 1964) and Japan (Hayashi, 1973). New statistical surveys and development projects made possible mostly American or British initiatives of applying CPT in African countries, such as Ghana (Grove & Huszár, 1964; Gould; McNulty 1969), Nigeria (Mabogunje, 1968), Kenya (Soja, 1968), South Africa (Carol, 1952; Davies, 1967) amongst many others. In South America, development projects in Peru, Chile (Berry, 1969), Colombia, or Bolivia also applied CPT, and the quantitative revolution spread through modernizing regimes as the case of Brazil suggests (Lamego, 2015; 2016). A number of comparative and critical works of applying CPT in the Global South appeared (e.g. Kuklinski 1978). In the socialist world, after the Stalinist purge of internationally renowned mathematical economics during the 1930s and 1950s, there developed a parallel “mathematical thrust” and growing East-West exchange during the détente of the 1960s (Jensen & Karaska, 1969; Saushkin, 1971). Soviet and Eastern Bloc reformism and the institutionalization of urban and regional planning in the mid-1950s summoned CPT in the service of centralized and long-term state planning, which ignited debates of adaptability between “socialist” and “capitalist” contexts, and also between domestic industrial or welfare policies (Ginelli, forthcoming). CPT strongly influenced the national urban and regional planning concepts of Eastern European countries, where it was already well known, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania (e.g. Perczel & Gerle, 1966; Vrišer, 1971). Apart from diffusing through Comecon plan coordination, socialist planning discourse borrowed from a transnational pool of knowledge. Quite remarkably, the seemingly “neutral” mathematical-geometrical language of CPT and the political demand for national development plans interweaved “socialist” and “capitalist” contexts, which held important continuities into the postsocialist era (Ginelli, forthcoming; in preparation). With the “new economic geography” emerging in the 1990s, the already developed canon of location theories such as CPT were solidified in neoclassical economics and neoliberal policies connected to a new regionalism.

Drawing on a number of such case studies, this book project aims to connect, contest, and contribute to various fields in the history of scientific knowledge. First of all, it explores the global histories of geography, regional science, urban studies, economics, and related fields in a period marked by geopolitical transitions such as the Second World War, decolonization, and the end of the Cold War. Arguing for a global discourse of CPT, this book contests current disciplinary accounts by re-addressing issues of narrativity, historical periodization, and geographical foci. It aims to broaden the fields of intellectual history and the sociology of science by connecting to the approach of science and technology studies to trace the spatial biographies of various actors, including people, ideas, theories, data, practices, technologies, or capital (e.g. Daston 2000). The yet unwritten transnational history of CPT and spatial analysis fits into the burgeoning literature on the transnational histories of Cold War technosciences, such as mathematical economics, statistical analysis, cybernetics, ekistics, systems theory, linear programming, game theory, or diffusion analysis (e.g. Andersson & Rindzeviciute 2015). This book also contributes to the growing studies of architectural history and policy mobilities, and the history of urban and regional planning with the aim to rethink postwar planning history (Ward, 2010; Wakeman 2014). On a further account, the book reveals the uneven power relations in global knowledge production and thereby adds to postcolonial and decolonial studies by decentering dominant Anglo-American knowledge production by focusing on interconnectivity and peripheralized contexts.

References

Andersson, J. & Rindzeviciute, E. (eds.)(2015): The Struggle for the Long-Term in Transnational Science and Politics: Forging the Future. London: Routledge.

Barnes, T. J. (2002): Performing economic geography: two men, two books, and a cast of thousands. Environment and Planning A, 34: 487–512.

Barnes, T. J. & Minca, C. (2012): Nazi Spatial Theory: The Dark Geographies of Carl Schmitt and Walter Christaller. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103(3): 669–687.

Barnes, T. J. & Abrahamsson, C. C. (2017): The imprecise wanderings of a precise idea: The travels of spatial analysis. In Jöns, H., Meusburger, P. and Heffernan, M. (eds.): Mobilities of Knowledge. Dordrecht: Springer. 105–121.

Berry, B. J. L. & Garrison, W. L. (1958): The functional bases of the central place hierarchy. Economic Geography,

34(2): 145–154.

Berry, B. J. L. (1969): Relationships between Regional Economic Development and the Urban System: The Case of Chile. Tijdscrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 60: 283–307.

Bosma, K. (1993): Verbindungen zwischen Ost- und Westkolonisation. In: Rössler, M., Schleiermacher, S. (eds.): Der “Generalplan Ost”: Hauptlinien der nationalsozialistischen Planungs- und Vernichtungspolitik. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. 198–214.

Brush, J. E. (1953): The Hierarchy of Central Places in Southwestern Wisconsin. Geographical Review, 43(3): 380-402.

Carol, H. (1952): Das Agrageographische Berachtungssystem. Ein Beitrag zur Landschaftkundlichen Methodik dargelegt am Beispiel der in Südafrika. Geographica Helvetica, 1: 17–67.

Christaller, W. (1933): Die zentralen Orte in Süddeutschland. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Clark, B. D. & Costello, V. (1973): The Urban System and Social Patterns in Iranian Cities. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 59: 99–128.

Cuyala, S. (2015): Mapping the sources of diffusion and the active movements of scientists by using a

corpus of interviews: An experiment about the origins of theoretical and quantitative geography in French-speaking Europe. Terra Brasilis (Nova Série), 5.

Davies, R. J. (1967): The South African urban hierarchy. South African Geographical Journal, 49(1): 9–20.

Daston, L. (ed.)(2000): The Biographies of Scientific Objects. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Dickinson, R. E. (1947): City, Region and Regionalism. London: Meuthen.

Duncan, J. C. (1955): New Zealand Towns as Services Centres. New Zealand Geographer, 11(2): 119–138.

Fehl, G. (1992): The Nazi Garden City. In: S. V. Ward (ed.): The Garden City: Past, Present and Future. Milton Park & New York: Taylor and Francis. 88–106.

Ginelli, Z. (in preparation) The historical geographies of the “quantitative revolution”: Towards a transnational history of central place theory. Ph.D. Dissertation. Budapest: Eötvös Loránd University, Faculty of Science, Doctoral School of Earth Sciences, Geography-Meteorology Program.

Ginelli, Z. (2018, forthcoming): Globalizing the “quantitative revolution”: The “technocratic turn” in geography and spatial planning in socialist Hungary. In: Idem (ed.) Technosciences of Post/socialism.

Ginelli, Z. (2018): Critical Remarks on the “Sovietization” of Hungarian human geography. In:

Godlund, S. (1951): Bus Services, Hinterlands and the Location of Urban Settlements in Sweden, especially in Scania. Lund.

Gregory, D. J. (1978): Ideology, Science and Human Geography. London: Hutchinson & Co.

Grove, D. J. & Huszár, L. I. (1964): The Towns of Ghana. Accra: Ghana Universities Press.

Gunawardena, K. A. (1964): Service centres in southern Ceylon. University of Cambridge, PhD Thesis.

Hayashi, N. (1973): On the Spatial Features of the Central Functions in Tokai Area. The Human Geography, 25: 26-52.

Istel, W. (2002): Zentrale Orte und ihre Einzugsbereiche. Theorien, empirische Untersuchungen, raumordnerische Anwendungen bis 1945. Ein Lese- und Lehrbuch in zwei Teilen. Tl.1. Prae Christaller. Zentrale-Orte-Theorien und empirische Zentralitätsuntersuchungen zwischen 1809 und 1933/34. Entmytholosierung einer Theorie, München : Fachgebiet Raumforschung, Raumordnung u. Landesplanung, Techn. Univ. München.

Jensen, R. G. & Karaska, G. J. (1969): The mathematical thrust in Soviet economic geography: Its nature and significance. Journal of Regional Science, 9: 141–152.

Kant, E. (1935): Bevölkerung und Lebensraum Estlands. Ein Anthropoökologischer Beitrag zur Kunde Baltoskandias. Tartu: Akadeemiline kooperatiiv.

Kegler, K. R. (2015): Deutsche Raumplanung. Das Modell der “Zentralen Orte” zwischen NS-Staat und Bundesrepublik. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh.

Kuklinski, A. (ed.)(1978): Regional Policies in Nigeria, India and Brazil. The Hague: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lamego, M. (2015): Genius loci Duas versões da geografia quantitativa no Brasil. [Genius loci: two versions of quantitative geography in Brazil.] Terra Brasilis (Nova Série), 5: 1–14.

Lamego, M. (2016): Sobre a geografia da ciência: perspectivas locais e transnacionais nas histórias da geografia quantitativa brasileira. [On the geography of science: local and transnational perspectives in Brazilian quantitative geography]

Livingstone, D. N. (1992): The Geographical Tradition: Episodes in the History of a Contested Enterprise. Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Livingstone, D. N. (2003): Putting Science in Its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lösch, A. (1939): Die räumliche Ordnung der Wirtschaft. Eine Untersuchung über Standort, Wirtschaftsgebiete und internationalem Handel. Fischer, Jena.

Mabogunje, A. L. (1968): Urbanization in Nigeria. London: London University Press.

McNulty, M. L. (1969): Urban Structure and Development: The Urban System of Ghana. Journal of Developing Areas, 3: 159–176.

Michel, B. (2016): Strukturen Sehen. Über die Karriere eines Hexagons in der quantitativen Revolution. Geographica Helvetica, 71: 303–317.

Nicolas, G. (2009): Walter Christaller From “exquisite corpse” to “corpse resuscitated”. SAPIENS, 2.2.

Nicolas, G. & Radeff, A. (2015): Walter Christaller: les “principes” (“Prinzipien”) d’un géographe totalitaire opportuniste. Cyberato, Alter-perspectives disputables, Rubrique: Publications, Travaux et Mémoires, août 2015. www.cyberato.org

Perczel, K. & Gerle, G. (1966): Regionális tervezés és a magyar településhálózat [Regional Planning and the Hungarian Settlement Network]. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Perera, N. (2010): When Planning Ideas Land: Mahaweli’s People-Centred Approach. In: P. Healey & R. Upton (eds.): Crossing Borders: International Exchange and Planning Practices. London & New York: Routledge. 141–172.

Radeff, A. (2012): Hexagones sans centre, centres sans hexagone. Géographes de langue allemande et système christallérien, 1933-2010. [Hexagons without center, centers without hexagon. German speaking geographers and Christallerian system, 1933–2010.]

Rössler, M. (1989): Applied geography and area research in Nazi society: Central place theory and planning, 1933–1945. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 7: 419–431.

Saushkin, Y. G. (1971): Results and prospects of the use of mathematical methods in economic geography. Soviet Geography, 12(4): 416–427.

Skinner, G. W. (1964): Marketing and social structure in rural China. Journal of Asian Studies, 34.

Smailes, A. E. (1944): The urban hierarchy in England and Wales. Geography, 29(2): 41–51.

Soja, E. W. (1968): The Geography of Modernization in Kenya: A Spatial Analysis of Social, Economic, and Political Change. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Trezib, N. (2014): Die Theorie der zentralen Orte in Israel und Deutschland: Zur Rezeption Walter Christallers im Kontext von Sharonplan und “Generalplan Ost”. Oldenbourg: De Gruyter.

Van Meeteren, M. (2018, forthcoming): Statistics do sweat: Situated messiness and spatial science. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers.

Van Meeteren, M. & Poorthuis, A. (2018): Christaller and “big data”: recalibrating central place theory via the geoweb. Urban Geography, 39(1): 122–148.

Van Meeteren, M. (in preparation) Writing blue notes in the march of geographical history: Revisiting the 1960 Lund Seminar in Urban Geography.

Vrišer, I. (1971): The pattern of central places in Yugoslavia. Tijdschrift voor economische sociale geographie, 62: 290–300.

Wakeman, R. (2014): Rethinking postwar planning history. Planning Perspectives, 29(2): 153–163.

Ward, S. (2010): Transnational Planners in a Postcolonial World. In: P. Healey & R. Upton (eds.): Crossing Borders: International Exchange and Planning Practices. London & New York: Routledge. 47–72.

Withers, C. W. J. (2009): Place and the “Spatial Turn” in Geography and History. Journal of the History of Ideas, 70(4): 637–658.