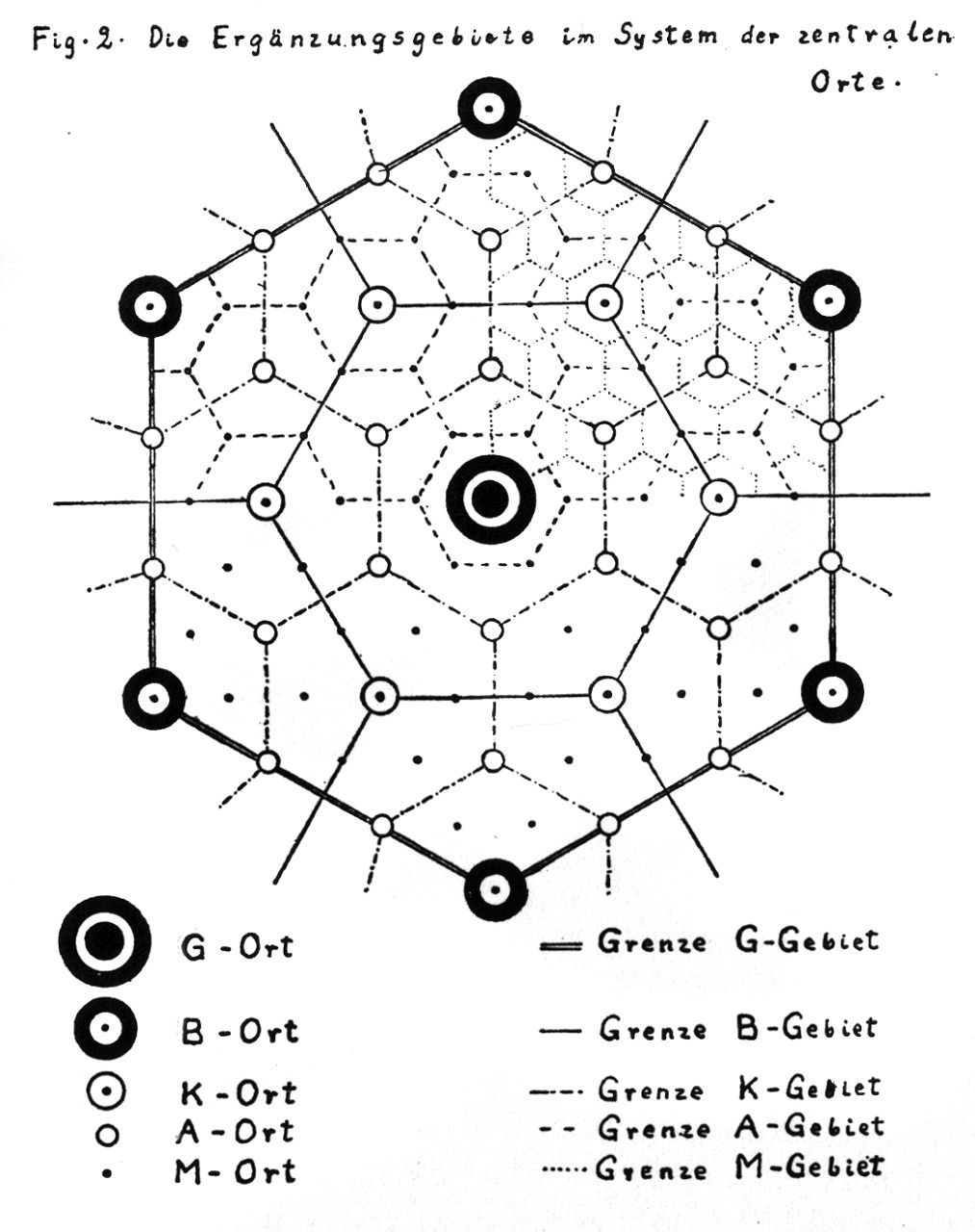

In textbook chronicles, the “quantitative revolution” marked a historical moment when geography became a true Cold War science. As a result of the Second World War, a new generation of geographers left their parochial disciplinary chambers and idiographic methods to turn towards an interdisciplinary approach by adopting the universal “scientific method”, and pursue rigorous, testable mathematical methods in spatial analysis and a positivistic urge to apply deductive theories in spatial planning, modernization and development. An inevitable element of this change was the (re)discovery of German location theories (von Thünen 1826, Weber 1909), including the central place theory of Walter Christaller (1933) and August Lösch (1940), which revolutionized the field of urban geography and regional planning.

However, anti-positivist critique in the West since the late 1960s has greatly simplified these historical contexts, and the knowledge geographies, wider geographical conditions and knowledge networks of the “quantitative revolution” have remained unexplored. The “revolution” was actually an emerging hegemonic narrative of academics in the global center of North America and Britain, who appropriated interwar era German location theories for their own local pursuits with the help of their postwar academic alliance with Swedish geographers.

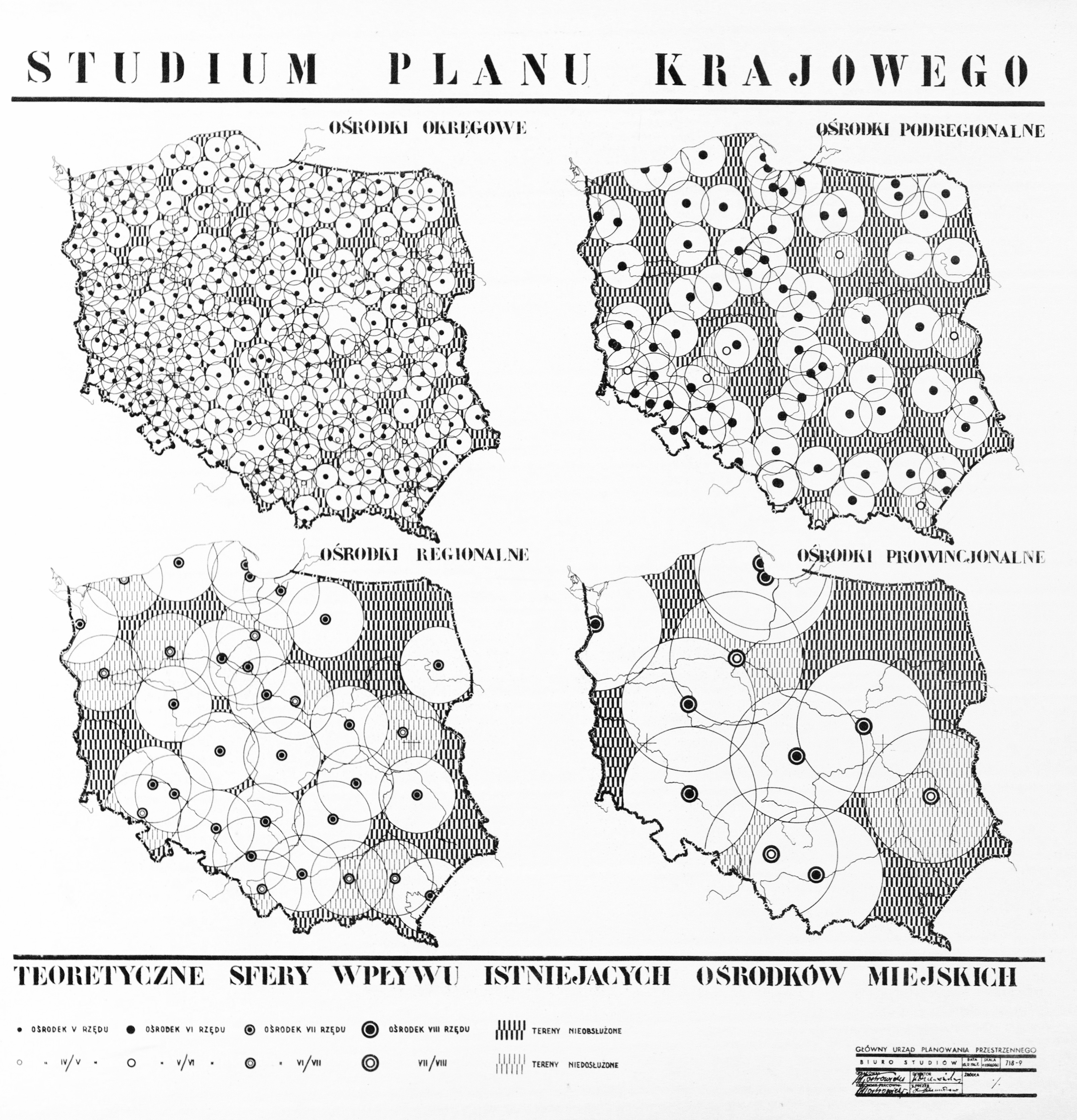

But missing from this transnational history is the early postwar school of Polish geography and spatial planning, which became an important precursor in the wider history of the centralized state being involved in the regional planning of settlements. This article shows how the various contexts of European state-led applications of central place theory – disregarded by liberal capitalists in the West – connected across statist regimes, by focusing on how Walter Christaller’s central place theory was applied in the German colonization of Poland by the Nazis during the Generalplan Ost (1940–43) and then in postwar Polish spatial planning under the nation-wide reconstruction orchestrated by the National Office of Spatial Planning (1946–48), which relied on this same German planning knowledge. The remarkable continuity between the Nazi German and postwar Polish contexts gave Polish geographers an advantage to be later included in the American-led Western knowledge networks of the “quantitative revolution” from the late 1950s on, despite the Iron Curtain.

© Copyright – Content is protected by copyright!

Citation:

Ginelli Z. (2020): The forgotten Polish link in the global history of the “quantitative revolution”. Critical Geographies Blog, 2020.01.01. Link: /2020/01/01/the-forgotten-polish-link-in-the-global-history-of-the-quantitative-revolution/