Introduction

Why did the West develop? This module is a research-intensive and practice-based seminar in global history, focusing on some popular debates which considerably stirred up academic circles around this question. Module topics revolve around key issues in global history, such as colonialism and imperialism, the rise of the West, global development and Eurocentric history. Our schedule begins with two introductory classes serving to equip students with the basic knowledge, concepts and methods for discussions. The bulk of the module consists of six debate sessions, in which students are asked to form groups and prepare for each discussion based on the session topic. Assessment is primarily based on debate performance and a short summary report covering their discussion inputs. Students interested in the social sciences or the humanities, especially history, geography, international relations, economic history, development studies and political science and who are wishing to advance their argumentative skills are highly encouraged to apply.

Literature

Allen, R. C. (2011): Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blaut, J. M. (2000): Eight Eurocentric Historians. New York: The Guilford Press.

Blaut, J. M. (1993): The Colonizer’s Model of the World: Geographical Diffusionism and Eurocentric History. New York: Guilford.

Clayton, D. (2009a) Colonialism. In: Gregory, D., Johnston, R. J., Pratt, G., Watts, M., Whatmore, S. (eds.): The Dictionary of Human Geography. (Fifth Edition.) Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. 94–98.

Clayton, D. (2009b) Imperialism. In: Gregory, D., Johnston, R. J., Pratt, G., Watts, M., Whatmore, S. (eds.): The Dictionary of Human Geography. (Fifth Edition.) Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. 373–374.

Conrad, S. (2016): What is Global History? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Daly, J. (2015): Historians Debate the Rise of the West. London, New York: Routledge.

Frank, A. G. (1998): ReORIENT: Global Economy in the Asian Age. University of California Press.

Jensen, L., Suárez-Krabbe, J., Groes, C., Pecic, Z. L. (eds.)(2017): Postcolonial Europe: Comparative Reflections after the Empires. Rowman and Littlefield.

Pomeranz, K. (2000): Introduction. In: The Great Divergence. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 3–27.

Potter, R. B., Binns, T., Elliott, J. A., Smith, D. (2009): Understanding colonialism. In: Geographies of Development: An Introduction to Development Studies. (Third Edition.) Prentice Hall. 47–78.

Stanziani, A. (2018): Eurocentrism and the Politics of Global History. Palgrave Macmillan.

Young, R. J. C. (2001): Colonialism. In: Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction. Malden, Oxford, Carlton: Blackwell. 15–25.

Young, R. J. C. (2001): Imperialism. In: Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction. Malden, Oxford, Carlton: Blackwell. 25–44.

Module Schedule

| May 24 | Shopping Lecture | |

| June 7 | Session 1 | Debating Global History |

| June 14 | No Session | Conference leave |

| June 21 | Session 2 | Global History and Eurocentrism |

| June 28 | Session 3 | The Case for Colonialism |

| July 5 | Session 4 | Global Centrisms |

| July 12 | Session 5 | Why Only in the West? |

| July 19 | Session 6 | Geographical Determinism |

| July 26 | Session 7 | The Clash of Civilisations |

| To be decided | Session 8 | We Never Had Colonies |

Session 1 – Introduction I: Debates in Global History

Our first session introduces students to global history and overviews some significant approaches and debates in the subject. The first session also familiarises students with the method of mind mapping and moderated discussion for forthcoming sessions.

Reading:

Stanziani, A. (2018): Why We Need Global History? In: Eurocentrism and the Politics of Global History. Palgrave Macmillan. 1–20.

Session 2 – Introduction II: Global History and Eurocentrism

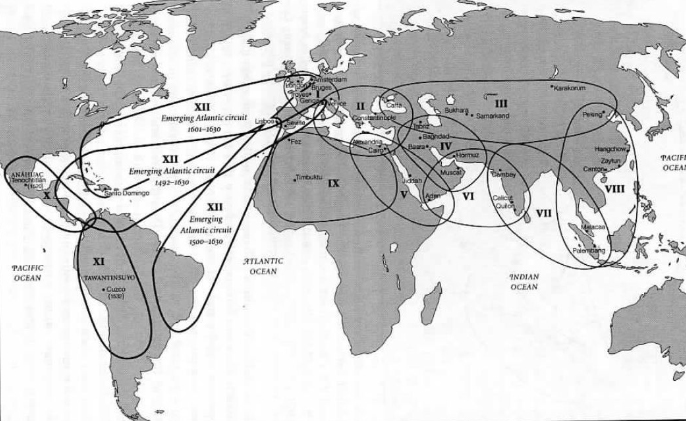

Our second session offers a nutshell overview of ways to engage with global history, its methods (global scale, transnationalism, comparativism, interconnectivity) and basic concepts (colonialism, imperialism, modernity, capitalism), and elaborates on the issues of Eurocentrism and other global centrisms.

Reading:

Conrad, S. (2016): Competing Approaches. In: What is Global History? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 37–61.

Session 3 – The Case for Colonialism

Statement: Colonies benefited from colonialism and imperialism.

Context: An article by Bruce Gilley (Professor of Political Science at Portland State University) published in the opinion section of the journal Third World Quarterly argued that colonialism as a system was ultimately beneficial for colonies, since it provided order and development, and some of colonialism’s merits and legitimacy should be reconsidered today in order to battle current weak states and inequalities in the postcolonial world. The article was met with huge upheaval and harsh criticism, and after a series of scandalous incidents (at one point half of the editors stepped down to protest against unscientific procedure) it was ultimately withdrawn from the journal. Was his argument generally flawed, or can it provide some valuable insights or conclusions? Was it worth to be part of colonial empires?

Focus text: Gilley, B. (2017): The case for colonialism. Third World Quarterly, 1–17.

Supplement:

What have the Romans ever done to us?

Bruce Gilley’s lecture:

Heleta, S. (2017): The Third World Quarterly debacle. Africa Is a Country, 24 September. http://africasacountry.com/2017/09/the-third-world-quarterly-debacle

Robinson, N. J. (2017): A quick reminder of why colonialism was bad. Current Affairs, 14 September. https://www.currentaffairs.org/2017/09/a-quick-reminder-of-why-colonialism-was-bad

Wills, J. H., Salazar, R., Leung, C.: Call for Apology and Retraction from Third World Quarterly. https://www.change.org/p/third-world-quarterly-call-for-apology-and-retraction-from-third-world-quarterly

Wood, P. (2017): The Article that Made 16,000 Ideologues Go Wild. Minding the Campus, 4 October. https://www.mindingthecampus.org/2017/10/the-article-that-made-16000-profs-go-wild

Session 4 – Global Centrisms

Statement: Global history is fundamentally Eurocentric, so we must decolonise our knowledge.

Context: One of the most recurring debates on global history is about Eurocentrism and “decolonising” our knowledge and canonised historical curricula. Anti-Eurocentric critics have argued that the European perspective of historical development has been uncritically priviliged and universalised as a model to narrate world history. However, it is not clear how we may define a non-Eurocentric approach and its limits, since history has always been written from concrete geographical positions. This may result in “essentializing”a particular culture, ethnicity or geographical position, as seen in the rivaling “centrisms” of continentalist approaches, such as Afrocentrism, Sinocentrism, Indocentrism etc. How can we imagine a non-Eurocentric global history, and what are the problems of “decolonising” our supposedly Eurocentric assumptions of world development? From whose perspective should global history be told or “decolonised”, considering various colonial heritages and the unequal positions of representation?

Focus text: Conrad, S. (2016): Chapter 8: Positionality and Centered Approaches. In: What is Global History? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 162–184.

Supplement:

https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern/decolonise-history-curriculum-education-how-meghan-markle-black-study

https://discoversociety.org/2019/02/06/navigating-the-decolonising-process-avoiding-pitfalls-and-some-dos-and-donts

https://www.facebook.com/pg/DecoloniseCambridge

https://www.facebook.com/DecolonisingOurMinds

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/oct/25/cambridge-academics-seek-to-decolonise-english-syllabus

Session 5 – Why Only in the West?

Statement: The rise of the West was due to its unique characteristics and internal development.

Context: Many authors who have written on the global development history came to the conclusion that the rise of the West can ultimately be explained by its unique social, cultural, political or economic characteristics compared to other cultures and societies. The noted economic historian David Landes argued – following Max Weber, amongst others – that the West outpaced other societies due its distinctive character of values and institutions, and its inventiveness leading to innate technological progress. But is it legitimate to say that the West developed only due to some of its “innate” characteristics, and can “internal” and “external” factors be separated at all?

Focus text: Landes, D. (1998): The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some are So Rich and Some So Poor? New York: W. W. Norton.

Supplement:

Blaut, J. M. (2000): Chapter 9: David Landes: The Empire Strikes Back. In: Eight Eurocentric Historians. New York: The Guilford Press. 173–199.

Hobson, J. M. (2004): The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

http://studien-von-zeitfragen.de/reOrient/html/frank_on_landes.html

Duchesne, R. (2001–2002): Between Sinocentrism and Eurocentrism: Debating Andre Gunder Frank’s Re-Orient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Science and Society, 65(4): 428–463.

Frank, A. G. (1998): ReORIENT: Global Economy in the Asian Age. University of California Press.

Session 6 – Geographical Determinism

Statement: Geography and the natural environment was responsible for the rise of the West.

Focus text: Diamond, J. (1997): Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. Los Angeles: University of California. Chapter 10: Spacious Skies and Tilted Axes. 176–191.

Context: One of the most popular explanations for the rise of the West was Europe’s favorable (temperate) climate and land, advantageous biological environment, and better geographical position. In similar vein, Jared Diamond argued that the course of global history and development inequalities has been strongly determined by the natural environment: the shape of continents, geographical accessibility, domesticable animals, cultivable plants, and the diffusion of various viruses and bacteria. But is this not just plain geographical determinism? What geographical factors have conditioned global development, and what are the limits to a geographical explanation to global history, compared to other cultural, social or economic factors?

Supplement:

http://www.jareddiamond.org/Jared_Diamond/Geographic_determinism.html

Blaut, J. M. (2000): Chapter 8: Jared Diamond: Euro-Environmentalism. In: Eight Eurocentric Historians. New York: The Guilford Press. 149–172.

Correia, D. (2013): F**k Jared Diamond. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 24(4): 1–6.

Hong, S. (2010): Chapter 8: Environmenal and Geographic Determinism: Jared Diamond and His Ideas. In: Wiarda, H. J. (ed.): Grand Theories and Ideologies in the Social Sciences. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 141–158.

McNeill, J. R. (2001). The World According to Jared Diamond. The History Teacher, 34(2): 165–174.

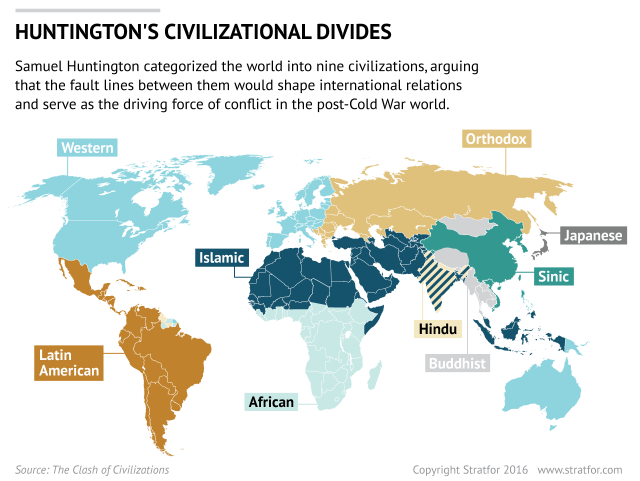

Session 7 – The Clash of Civilisations

Statement: The essential characteristics of civilisations lead to inevitable and irreconcilable conflicts.

Context: In the post-Cold War era from the 1990s on, it has become evident that decades of postcolonial migration have fundamentally changed the cultural relations of metropole societies, while geopolitical power struggles and capitalist globalisation have spawned various forms of cultural opposition to the West, including Islam fundamentalism. Samuel P. Huntington’s seminal article and book argued that in this new era the waning of the Cold War bipolar world order of socialist and capitalist countries gave way to a new logic: the clashes of civilisations. “Human history is the history of civilisations. It is impossible to think of the development of humanity in any other terms.” (Huntington 1996: 40) But can global history be understood as a history of civilisations, and is it legitimate to conceptualise the development of human societies as civilisational conflicts?

Focus text: Huntington, S. P. (1993): The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs, 72(3): 22–49.

Huntington, S. P. (1996): The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Supplement:

Source: https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/why-civilizations-really-clash

Foreign Affairs (2010): The Clash of Civilizations: The Debate. (Second Edition.) New York: Foreign Affairs. http://www.scholarsglobe.org/uploads/7/2/1/5/7215173/the_clash_of_civilizations_the_debate.pdf

Said, E. W. (2001): The Clash of Ignorance: Labels like “Islam” and “the West” serve only to confuse us about disorderly reality. Nation, 4 October. https://www.thenation.com/article/clash-ignorance

Said, E. W. (1993): The Myth of the „Clash of Civilizations”. University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

text: https://archive.org/details/edward_201604; lecture:

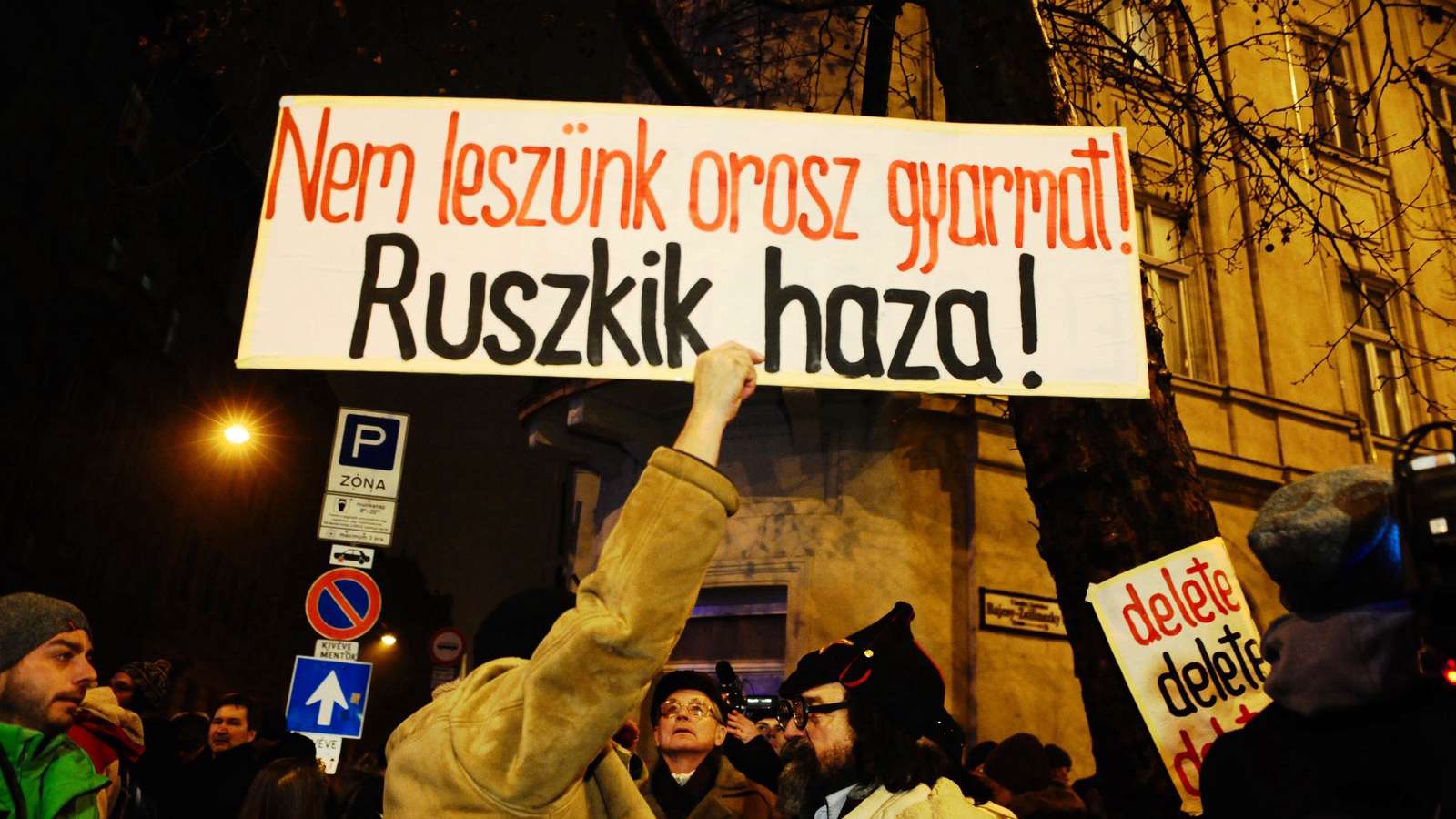

Session 8 – We Never Had Colonies

Statement: We never had colonies, so we are not responsible for the consequences of colonisation.

Context: Not all national histories regard themselves as belonging to global colonial history, in fact some argue that they never had colonies and did not pursue imperialism at all, thus they are not responsible for the fate of colonies, postcolonial inequalities and migration. In recent years, this argument has become very popular in political debates around globalisation, nationalist identity politics, racism, restricting global migration and strengthening national sovereignty (especially in Europe and the USA). On the other hand, some nations pursuing this argument victimise their country as having been historically colonised by various empires (Ottoman, Hapsburg, German, British, French, Soviet etc.) or forces of globalisation and global capitalism in global history. What might motivate certain countries to pursue the above argument and why? Are there countries without a colonial history, and is it worth to be part of global colonial history? Are these countries right in asserting that they have no connections to colonial and imperial history and have no responsibility for the consequences of colonialism?

Focus text: Various interviews and speeches in current media – see module assignment for materials.

Supplement:

Preparation

In preparation, students are obliged to read the basic discussion text. Individual and collective research is expected on the author, the context of the text, its main theses and – most importantly – its criticism. They are free to use any online sources, including Wikipedia articles, news and journalist articles, academic journal articles, textbooks, and book chapters, but making use of provided supplement material is strongly advised. Students are also advised to use the time of the two introductory sessions to prepare and organise teamwork for the discussion sessions.

Tips for group preparatory work:

- Communicate! Create discussion groups and use social media to communicate. One efficient method is to form a closed group in social media (e.g. Facebook) to communicate with each other, have personal or online meetings (Messenger, Skype etc.), and create a Google Drive document where you can collect and organise materials, take notes and write up arguments collectively (you can use chat and commenting).

- Organise work and share knowledge! Discuss and decide your competencies amongst each other and share knowledge. One may be better at gathering materials, reading, critical analysis, structuring arguments, writing, or debating and performing. If you know something or have developed a particular interest in a topic, be sure to share with others, do not keep it to yourself! Not everyone has to read the same texts, with efficient groupwork you can minimise individual workload and maximise coverage of a given topic.

- Do the research! Good research and well-mined knowledge is the essence of a good debate.

- Choose your focus and arguments wisely! Keep in mind that each topic may be successfully criticised from various positions and through different methods – there are no golden rules. Put in effort to choose your approach and the concrete aspects you wish to focus on, and develop your argument design in that concrete direction. If you include too much, you may either run out of time or your overall argument might become unbalanced or defocused.

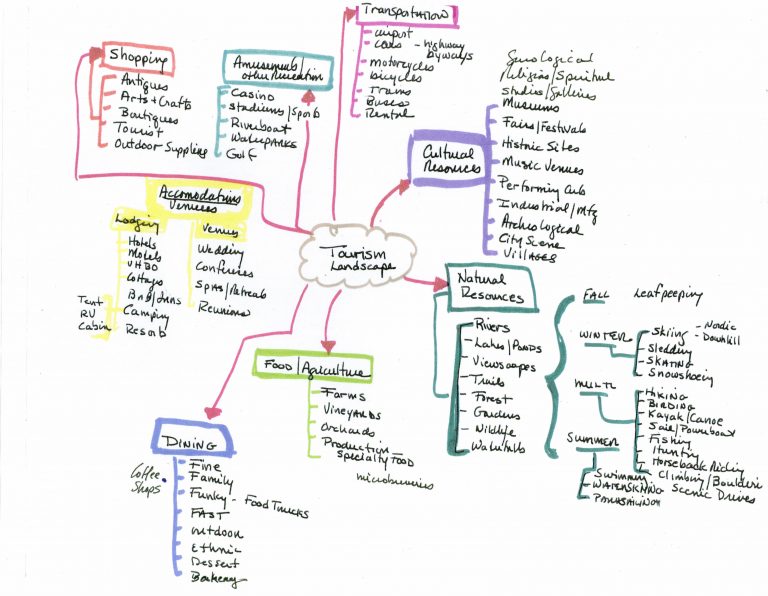

- Draw! An important element of discussions is the visualisation of your argument design. Be sure to prepare your mind map designs in forward, and experiment with new ways to effectively summarise and communicate your arguments in visual format. Use visual elements, like proper highlighting, colours or any relevant imagery that may be included on the whiteboard.

Designing arguments

A good critical analysis is not just about negative critique, trying to prove why the author or statement is biased and should be dismissed. Critical analysis should first present the basic ideas of the target author, why these became popular or in what ways they might be useful or compelling. Since discussion topics are rather wide, teams should focus only on a few key concepts and a set of well-selected arguments and evidence. Their argument design should be clear, organised and convincing, and show evidence of thorough research.

Mind Mapping

Mind mapping is a simple but efficient visual tool to brainstorm ideas and to organise, overview and present arguments. Students use markers on a whiteboard to draw up their mindmaps for each discussion during presentation. The basic mind map structure used here is a hierarchical, tree-like one: the middle concept or starting point of each mind map should be the main statement of the topic provided for each session. The map structure consists of:

- first-level core concepts (keywords) or main arguments;

- second-level and/or third-level subconcepts or subarguments containing detail and evidence;

- and these should be connected by hierarchical or flow-type lines that may be directional and may even form horizontal connections between subconcepts and subarguments.

Visuals may be moderately artistic, but various colouring or highlighting is strongly encouraged, and the focus should be on argument structure.

Discussion

Students form 2 teams. In each discussion session, both teams delegate students to given tasks:

- One member draws a mind map of arguments, while others speak.

- One member introduces the main approach, arguments, concepts and factors.

- One member explains the subarguments with evidence.

- If applicable, a fourth member may explain another set of subarguments with evidence.

- The mindmapper or another member sums up conclusions based on their argument model.

Time is strictly measured: it is up to team members to decide how they use up their time, but each team has a limit of 12 minutes. After presentations, the module leader overviews and compares both mind maps with students, and the class opens up to debate under the module leader’s moderation, where teams have to criticise the other teams’ arguments.

Evaluation

Attendance (10%): since this is a practice-based module, students are expected to show up at every class, otherwise absences may strongly affect their groups’ performance. Roll call and class activity are both included in evaluation. Missing more than 3 classes results in failing the whole module. Absences may only be accepted as valid if the student provides a valid reason and informs the Module Leader on Canvas the day before the teaching day.

Each team gets collective points for all six debates (10% each, 60% module total). The module leader takes photos of all mind maps and shares them on Canvas after each session, so they can be included in the final essay.

Discussion performance is evaluated by the following:

- style and convincingness of presentation;

- complexity of arguments and concepts;

- structured outline and logic of arguments;

- reliance on sound sources;

- innovativeness of approach;

- mind map design.

Each student gets individual points based on their personal activity (15%). These points are generated by students themselves, who fill in an anonymous sheet evaluating the work of their team members for each discussion. A student not active in class and proved to have totally ignored groupwork will fail the module.

Each team gets collective points for submitting a final essay, in which they summarise their debates (15%). The report should be an essay of exactly 6 pages, with each topic occupying 1 page of 500 words text (altogether 3.000 words). Submission deadline is 7th August 23:59 PM. See the Sample Essay in Files, and use this exact sample without modifying the format in any way. Mind maps should be included for each topic as an extra page. It is advised that groups create a Google Docs in which they work throughout the trimester, and then just refine their preparation notes for each discussion session to make up their final reports.

- Zero marks will be awarded to assignments which are clearly plagiarized from external sources.

- Late submission of the final assignment will result in 50% reduction in the obtained score.

- Non-submission will result in failing the module for all students in the group.