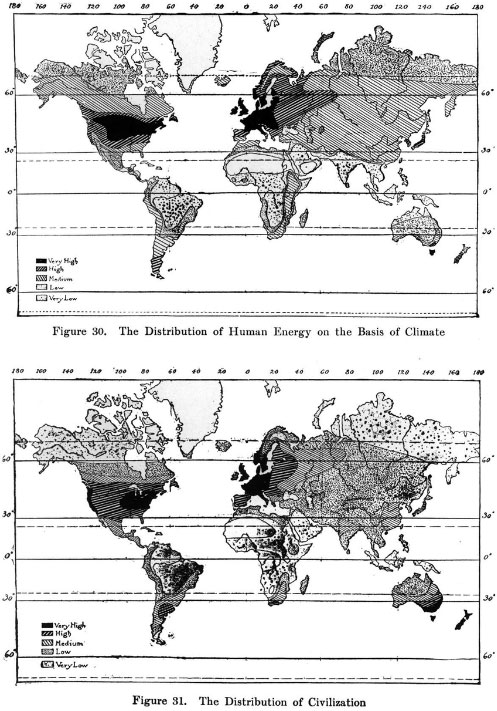

1935-ben a neves geográfus, Kádár László jelentetett meg egy tudományos ismeretterjesztő magazinban, a Búvárban cikket Afrika gyarmatosításának a történetéről. Néhány évvel később a magyar gyarmati tudástermelés az olasz és német gyarmati érdekek propagálása felé fordult, és élesszavú geopolitikusok (mint a németbarát Kalmár Gusztáv) kezdték mérlegelni, hogy Magyarország hogyan tudna ezen hatalmak afrikai térnyerésének farvizén érvényesülni. Ugyanabban az évben Kádár egy másik cikket is írt az olasz gyarmatosításról és Abesszíniáról, amit nemsokára lerohant az olasz hadsereg. Még Kádár viszonylag leíró és mértéktartó elbeszélését, amelyben olykor-olykor felbukkan az afrikai népek szabadságával szembeni halovány szimpátia is, lényegében nagy eurocentrikus narratívák uralják. Minden történelmi eseményt pusztán az európai hatalmak racionális és felvilágosult “döntéseire” vezet vissza, miközben az afrikai népek érdekeit, cselekedeteit és ellenállását elhallgatja. Afrika gyarmatiság előtti történelmét félreteszi, és az európaiak késői területi gyarmatosítását (a 19. század végétől) mindössze éghajlati és földrajzi tényezőkkel magyarázza, holott a valóságban az európaiak erős ellenállásba ütköztek a felfegyverzett afrikai államok részéről:

“Ennek az oka elsősorban a kontinens felszíne és éghajlata: partjai majdnem kivétel nélkül meredek, magas partok, amelyekre nehéz felkapaszkodni, a folyók is vízesésekkel zuhognak alá közvetlenül a torkolatuk előtt is, és így víziúton sem lehet a szárazföld belsejét megközelíteni. Északon a Szahara széles sivatagja is megközelíthetetlenné teszi az értékes Szudánt. Délen pedig a gyilkos trópusi klíma is erősen hátráltat. Ez magyarázza meg azt, hogy amikor Amerikában és Indiában már virágzó ültetvények voltak, Afrikát csak munkásembert szolgáltató kontinensnek tekintették és tovább nem érdeklődtek iránta.” (681. o.)

– ENGLISH VERSION –

HUNGARIAN GEOGRAPHERS PRODUCING COLONIAL KNOWLEDGE

In 1935, the noted geographer László Kádár published in a popular scientific magazine, Búvár about the history of colonizing Africa. A few years later Hungarian colonial knowledge production turned towards propagating Italian and German colonial interests, with rabid geopoliticians (such as the pro-German Gusztáv Kalmár) calculating how Hungary could follow up on the their promising trajectories in Africa. In the same year, Kádár also wrote another article about Italian colonies and Abyssinia, a country which was soon occupied by the Italian army. Even in Kádár’s rather descriptive and moderately toned account on African colonization, which was sprinkled with traces of distanced sympathy towards African independence, we can see grand Eurocentric narratives unfold. All historical events are simply based on the rational and enlightened “decisions” of European powers, without any account of the interests, actions and resistance of African people. The precolonial African history is sidelined, and the late territorial acquisitions of colonies in the continent (from the late 19th century) is explained by climatic and geographical factors, while Europeans met with the strong resistance of militarized African states:

“The main reason for this is the continent’s relief and climate: its shores are almost exclusively high and steep, which are hard to climb, and rivers plunge down in waterfalls even near the mouth, thus the internal lands cannot be reached through waterways. In the north, the wide desert of the Sahara makes the valuable Sudan inapproachable. In the south, the devastating tropical climate also forms an impediment. This explains that while in America or India there were already blooming plantations, Africa was seen as a continent offering manpower and remained of no further interest.” (p. 681)