Check out our panel at the ASEEES Summer Convention in Zagreb in 14-16 June 2019, to be held at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb.

Organizer: Zoltán Ginelli

How did Hungarian politics, in the name of “catching up” to the West, construct visions of development amidst structural change and global (re)integration, and how did these spark “culture war” and affect cultural solidarity and exchange? How did the idea of a “third way” political economic development in Hungary generate alternative and competing visions of cultural solidarity and alignment? How can we conceptualize these intertwined structural and discursive processes in Hungary by considering transnational and centre-periphery relations on various geographical scales? Our panel aims to address these questions by empirically exploring the role and relationship of intellectual experts and the state in Hungary after 1945, how their networks (re)organized along new alliances and conflicts due to wider political economic and discursive shifts.

The panel focuses on three main aspects. First, how state representatives, reformist intellectuals and ideologues tried to construct an alternative “third way” development politics in reaction to global restructuration and as a maneuver between East and West to reposition Hungary and Eastern (Central) Europe. Second, the “third way” is also a contested epistemological field in the analysis of the Hungarian path of semiperipheral development between accepted Western dichotomies (such as neoliberalism and authoritarianism, state and market, socialism and capitalism, East and West). Finally, the panel seeks connections between political economic shifts and cultural rearrangements, how new cultural politics were formed and how new forms of cultural solidarity or distinction evolved regarding space, class and race.

Keywords: Hungary, culture war, post-WWII period, third way development, intellectuals

SESSION 1

Chair: Gábor Danyi

Discussant: Stefano Bottoni

Anti-Germanism, and the definition of „New Hungary” 1945-46 – A special brand of „third world nationalism”?

Csaba Tóth

1945 was described at the time as a revolution and later as simply a „turning point” or „year zero” in the case of Soviet occupied Eastern European countries. As in Czechoslovakia or Poland, anti-German sentiments defined the first explanations of what happened and how to go forward in Hungary immediately after the Second World War. Those who then gained power were tasked with a difficult objective: reorganizing not only the state and its apparatus, but offer a new, credible identity to the people of Hungary itself. My presentation argues that they did so, mainly by importing anti-colonial sentiments, and trying to utilize them in a way that would legitimize Soviet occupation and the new regime as one that liberates Hungary from centuries of German domination. (Szekfű 1947; Révai 1948.) This interpretation invoked an early form of third world post-colonial sentiment known at the time from Indian and Chinese anti-colonial powers. Stalin himself oftentimes emphasized the pivotal importance of “national front struggles” against imperialism in China and India (Radchenko 2012) and this view and approach was strikingly similar to the Soviet Politburo’s standpoint on Hungarian and more generally, Eastern European struggles against Fascism and German domination. This approach had an effect on Hungary on the official level: not only in the form of the creation of a first and foremost nationalist “popular front” in 1944, and the definition of independence as “liberation”, but also on the focus on the expulsion of ethnic Germans, the rhetoric against Germans and “pro-Germans” (made similar to “Fascists”) during the first post-war years. Following previous ideas of “ethnic symbolism” (D. Smith 1987.) and ethnic myths as a nation-building historical force and the recognized effect decolonization made on Eastern European Consciousness as well as criticism of the established geographical restrictions on post-colonial studies (Owczarzak 2009; Spivak 1999) my study argues that a special kind of “Third Worldism”, anti-imperialism, and anti-colonialism is essential to understand the origins of post-1945 Hungarian “democratic” nationalism, prevalent to these days.

Geographical narratives as key elements of the culture war in Hungary

Péter Balogh

This contribution will show how a number of historically deeply rooted but competing geographical narratives exist in Hungary, which orient the country towards different geographic and ideational directions. Indeed, the gradual demise of consensus politics, which focused on European/transatlantic integration and market economy, has by the turn of the millennium given way to a culture war of some sort in several countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Trencsényi 2014). Yet despite being a small and ethnically relatively homogenous country, according to Janke (2013: 56) for instance Hungary appears more divided along ideological and geographical lines than e.g. Poland. Hungary is burdened by the conflict between the folkish and urbanite traditions, for instance, which goes back to at least the interwar period (Trencsényi 2014: 139). The notion of ‘Central Europe’ served pro-European aims and integration with the West in the 1980s and 1990s (Balogh 2017). There is a centuries-old image of the ‘Christian bulwark’ (Száraz 2012) against Muslims etc., recently mobilized during and after the 2015 refugee crisis. There is also a completely competing Turanian tradition since at least the beginning of the past century that emphasizes the Asiatic and Turkic roots of ancient Hungarians, and which was then as is nowadays deployed for hoped commercial and political benefits in Asia (Balogh 2015). It is argued that these narratives are both geographically and ideologically irreconcilable and form essential elements of the Hungarian culture war(s).

Post/colonial Hungary: Opening socialist Hungary to the “Third World”

Zoltán Ginelli

Eastern Europe is the “black sheep” of postcolonial studies, which focuses either on the global centre or the periphery, but silences Hungary’s complex historical relations and experiences to coloniality, colonialism and imperialism. This paper introduces the historical project of “post/colonial Hungary” in order to conceptualize Hungarian post/colonialities in semiperipheral development relations. This new approach criticizes constructivist approaches to postcolonialism in Eastern Europe by “speaking back” from the Hungarian semiperiphery and unearthing the forgotten density of local historical contexts and epistemological trajectories. The paper focuses on the post-1945 global realignment of Hungarian foreign policy, namely how Hungary’s turn towards Afro-Asian decolonization and the “Third World” induced a “cultural war” intertwined with visions for “third way” development under state-socialism, drawing parallels between postcolonial and Hungarian development history. Anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist solidarity contested previous civilizational and racial fault lines, but went hand-in-hand with the socialist civilizing mission in development assistance and pragmatic foreign economic maneuvering between East and West. Hungarian assistance to Non-Aligned Ghana led to founding the Centre for Afro-Asian Research (1963) under the economist József Bognár, who propagated export-oriented growth based on development experiences in postcolonial countries under the New Economic Mechanism. From the 1980s, the pro-West “back to Europe” turn and postsocialist market-liberal transition in Hungary silenced these historical relations with the postcolonial global periphery. Finally, the paper offers new insights into how a new “coloniality discourse” was based on complex historical experiences and appropriating postcolonial critique in the geopolitical maneuvering and “cultural war” of Viktor Orbán’s government after 2010.

SESSION 2

Chair: Péter Balogh

Discussant: Stefano Bottoni

The Prosecution of the Central Eastern European Neomarxist Opposition

Richárd Zima

The paper deals with the philosophers’ groups, which represented the Marxist alternative of the state socialist ideology and created the leftist opposition in countries like Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Yugoslavia. Most of these philosophers participated in the 1956 and 1968 movements, and in some cases, influenced them. Their philosophical and sociological research pointed out the real nature of state socialism. On that basis, their common aim was to find the ‘tertium datur’, the third way in opposition to the capitalist and the state-socialist order. The theoretic prosperity of the ‘60s ended with the prosecution of these groups as they fell victim to the cultural war initiated by their governments. This paper aims to provide insights into the intelligentsia’s prosecution caused by their critical description of the state socialism and, as a result of their attempt to seek alternatives, into the similarities and differences between their Neomarxist theories of the ideal society. The dissolution of this theoretical wave was a result of the political response to the aftermath of the Eastern European movements of 1968 as well as the dynamics of Soviet and world politics at the time. The differences among the processes of prosecution in the aforementioned countries will lead us to a deeper understanding of this Neomarxist opposition’s place in the complexity of Marxism itself. This would lead me to briefly introduce the rise of a new form (and generation) of leftist oppositional thought at the late ‘70s, which turned out to be less and less Marxist.

Transnational “Solidarity” in Poland and Hungary

Gábor Danyi

From the 1970s onwards, the transnational diffusion of ideas, techniques and strategies has helped to develop simultaneously the dissident movements in the Soviet-bloc countries. At this time the Hungarian democratic opposition from the establishment of the Polish Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR) sought contact with the Polish opposition. As a consequence the knowledge of alternative printing and the strategies of legalism, conspiring and non-violence were transmitted to small dissident circles in Hungary and under the influence of „new evolutionism” Hungarian intellectuals created parallel institutions, such as a flying university, legal aid service or alternative publishing houses. The tightening unofficial contacts between dissidents led to the emergence of a transnational dimension of solidarity in the bloc. However, it must be acknowledged that the very limited import of Solidarity movement in Hungary resulted in an asymmetry between these countries regarding the extension and patterns of cultural resistance and opposition. The paper interprets the new dissident practices and parallel institutions emerging in the 1980s in terms of “culture war” as far as they helped to form diametrically opposed ways of political and economic programs, geopolitical imagination and collective memory. Focusing on the history of Hungary and Poland the paper analyzes structural differences of the opposition movements and highlights the patterns of transnational/global solidarity.

German and American Political Assistance in Hungary: Western Development Models, Cultural Politics, and the Crises of Democratic Capitalism

Kyle Shybunko

When German political foundations and American “democracy promotion” outfits such as AID and the National Endowment for Democracy arrived in Budapest to help build a liberal democracy, they arrived in a country that was undergoing rapid political and constitutional change after years of party dictatorship. The chief tasks at hand were the democratization of politics, the promotion of an independent civil society, and the establishment of a market economy. Hungary would be returned to Europe. They also arrived in a society with a history of kulturkampf dating to the late 19th century when Hungarian liberals and Catholic nationalists spoke of a war for Hungary’s sovereignty fought on the terrain of culture, ethnicity and confession. Hungary’s new pluralistic politics was implicated by a revived version of this “culture war” which, like both its fin-de-siècle and interwar versions, was fundamentally tied to competing ideas of Europe and Hungary’s European-ness. How did these West German and American organizations navigate this Hungarian landscape which was otherwise understood to be the most promising and fertile in the New Europe with its rich tradition of reform economics? By examining the grant-making practices of these organizations in the 1980s and 1990s I show how funders approximated the political orientation and programs of civic organizations and incipient political parties, and how they understood cultural politics to be epiphenomenal to the urgent work of democratic capitalist transformation, missing in-fact the geopolitical and political-economic valences of these “culture wars” which are only so apparent at the current juncture.

The Ghetto as a Mobile Technology: Problematizing Gettósodás/Ghettoization in Budapest’s Eighth District after the Neo-Liberal Turn

Jonathan McCombs

This paper explores the transnational connection between racial regimes in the United States and Hungary to highlight how urban scholars and policy experts have sown racial and cultural divisions through the discursive concept of the ‘the ghetto.’ Inner city areas in the United States in the 1970s saw an increase in the concentration of very low-income, highly segregated black communities. In a bid to make sense of the worsening condition for inner city blacks in the US, scholars began describing these new urban spaces as ‘ghettos’ to account for the strong majority of racialized minorities (over 90%) living in these spaces and the limited life chances that ghetto inhabitants were afforded. Twenty years later, as Hungary underwent its own form of neo-liberalization, the discourse of ghettoization was picked up by scholars and policy makers to describe the conditions of inner-city Budapest districts that had come to be inhabited by a large Roma population and had been badly disinvested during state-socialism. In this presentation I focus on the Eighth District, which has been heavily stigmatized by experts as a ghetto since the early 1990s and has undergone state-led gentrification projects to curb the so-called ghettoization process. I show how the ghetto narrative was articulated in Hungary as a mobile technology of racial government, describing how it inflamed existing racialized divisions, igniting a culture war waged by policy makers and the local Eighth District government against Eighth District residents.

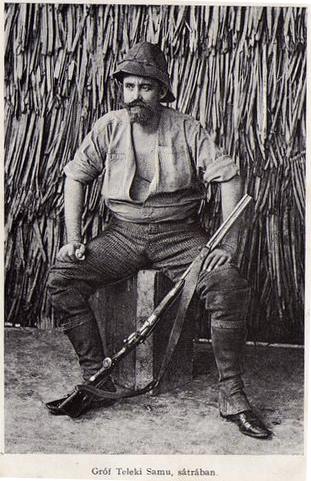

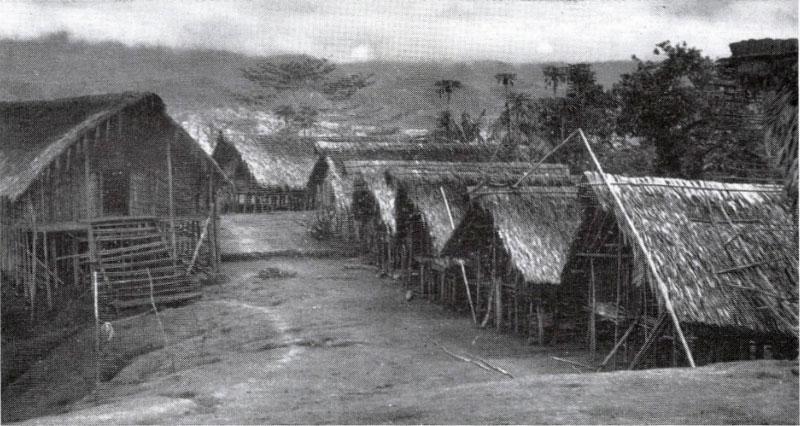

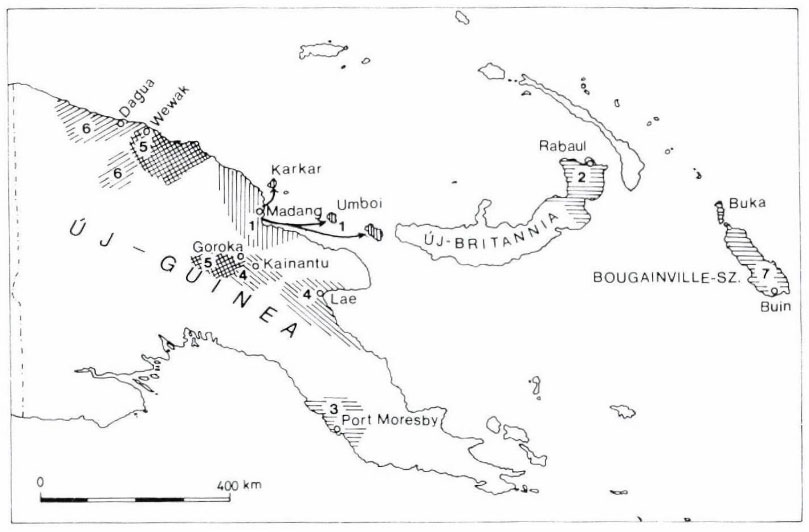

The working districts of Hungarian doctors: 1. Dr. András Becker; 2. Dr. Károly Haszler; 3. Dr. János Loschdorfer; 4. Dr. Károly Mészáros; 5. Dr. Lajos Róth; 6. Dr. Alajos Szymicsek; 7. Dr. Ferenc Tuza.

The working districts of Hungarian doctors: 1. Dr. András Becker; 2. Dr. Károly Haszler; 3. Dr. János Loschdorfer; 4. Dr. Károly Mészáros; 5. Dr. Lajos Róth; 6. Dr. Alajos Szymicsek; 7. Dr. Ferenc Tuza.