This research explores how Hungarians on both sides of the Iron Curtain opened up to Afro-Asian decolonisation through competing constructions of Eastern European semiperipheral postcoloniality. Eastern Europe has been excluded from global colonial history, which only accounts for the relationship between the global center and periphery, the colonisers and colonised. But the remarkable neglect of the region’s colonial history stems from its semiperipheral position. For Eastern Europe, the contradictory position of being part of the global center but also contesting it by allying with the periphery, being a colonial collaborant of White Empire but also critiquing or fearing Western colonialism resulted in an contradictory, in-between semiperipheral manoeuvring within the global world system. While recent studies in global history have dealt more and more with the relationship between the Second and Third Worlds during the Cold War, none of these analyses looked at the parallels and interactions between communist and anti-communist trajectories of colonial discourse and anti-colonialism in light of this Eastern European semiperipheral dynamic.

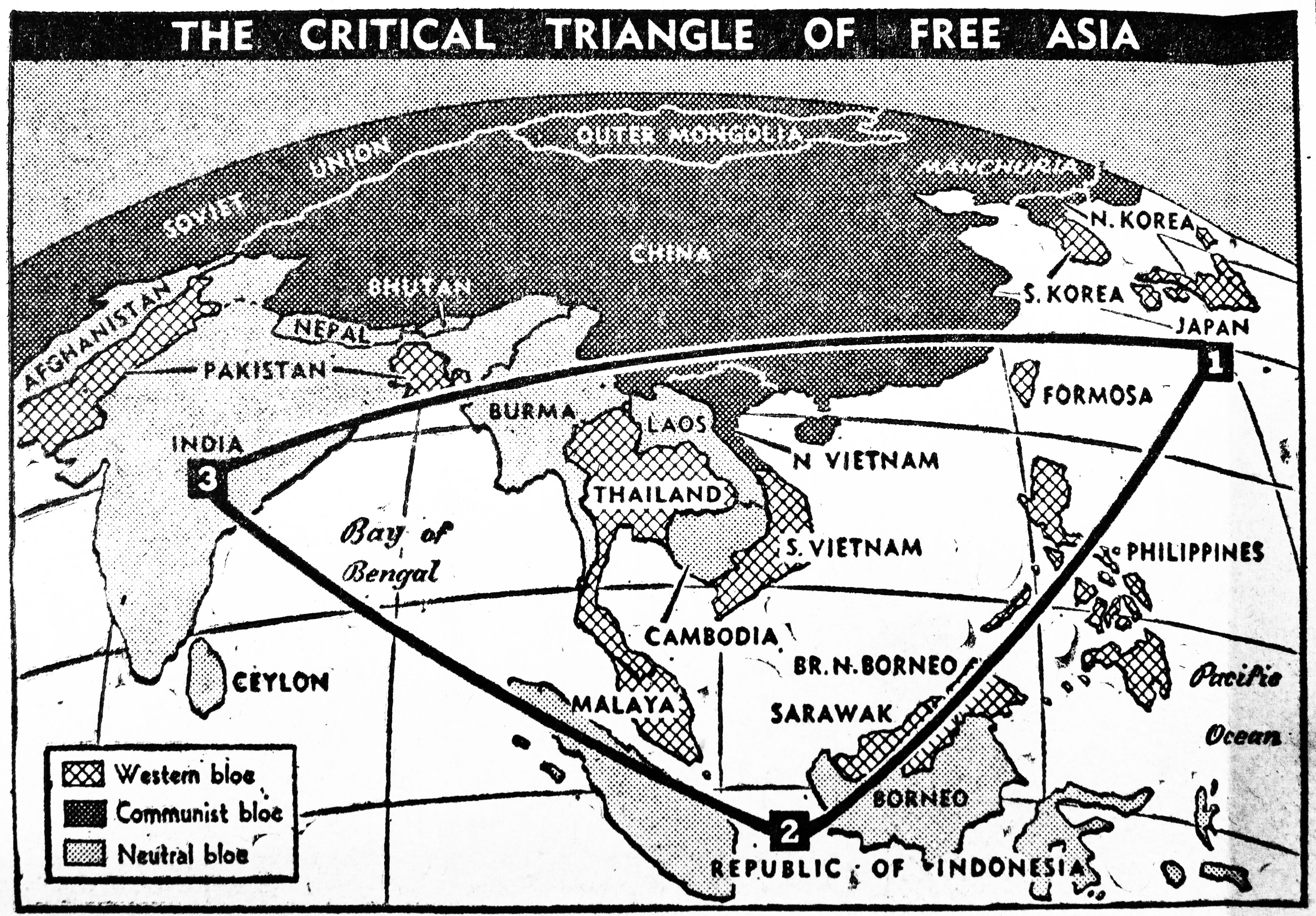

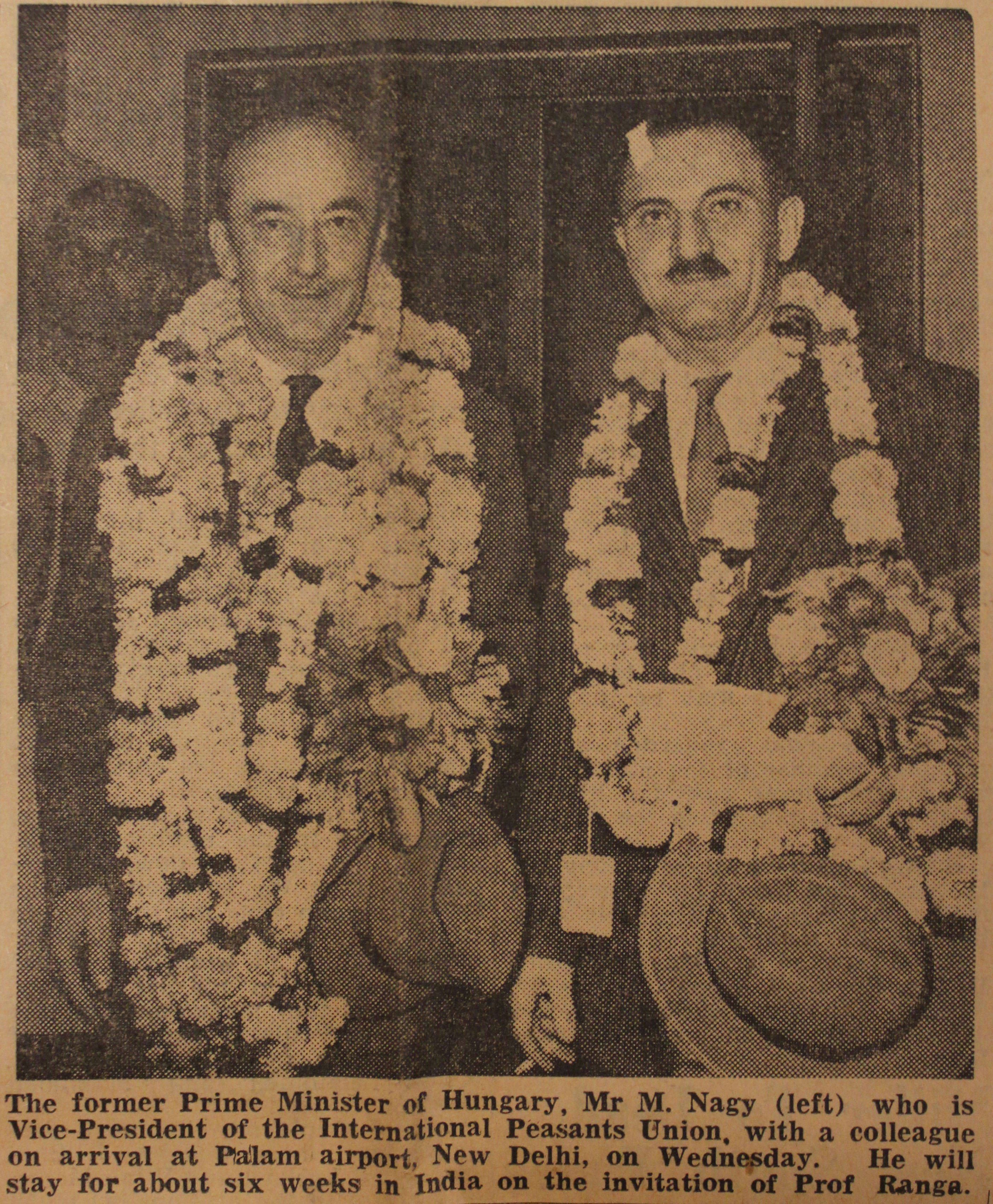

State-socialist Hungary struggled to open up via socialist globalisation against Western protectionism, and developed anti-colonialism against Western Empire and solidarity towards emerging postcolonies. The stakes were high, because Hungarian anti-communist political refugees in the West were already racing to first develop anti-colonial solidarity towards postcolonial countries and persuade them against “Soviet colonialism”. Backed by the USA, Hungarian ex-premier and Smallholders’ Party leader Ferenc Nagy successfully popularised this line of critique in the International Peasant Union and the Assembly of Captive European Nations. Between 1954 and 1955, Nagy toured parts of Asia, including India, Japan, Pakistan, the Philippines, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Thailand, Burma, and Ceylon, and spoke with the ambassadors of various other non-European countries, in order to manipulate the outcome of the first conference of postcolonial countries in Bandung (1955). Eventually, he was successful. During his Asian trip, he emphasised the need for enlightening propaganda on Soviet communism and gave various speeches on “Russian colonialism in Europe”, which was met positively by local politicians and was extensively covered by local newspapers. Many Asian postcolonial countries – with a majority of religious, mainly Muslim populations – feared Soviet and Chinese communist expansion, and the Hungarian intervention convinced them to put forward the critique against “Soviet colonialism” – causing great surprise and panic in the socialist bloc. As Nagy argued,

“I used the anti-colonialist sentiment to present the Soviet Union as the most brutal colonial power, which colonised ten countries at a time when the Western powers freed more than ten countries from colonialism. In all meetings and press conferences I claimed that India should also include the liberation of Eastern European countries in the fight against colonialism. (…)

The people’s right to sovereignty means the disintegration of colonialism and imperialism. The Asian and African nations would make a serious mistake, if they only demanded the liberation of the old colonies, but not the new communist colonialism. The old colonialism is currently being disposed. After the war, decolonisation liberated 600 million people.

But why did decolonisation stop? Because on the other hand the Soviet colonized 100 million European people. The most important requirement of the annihilation of old colonies is the disintegration of Soviet colonies. This view must clearly come out from the Bandung resolution, because otherwise the resolution against colonialism would become unreal.”

In the race for postcolonial recognition, the communist leadership in Hungary was losing initiative. The country could not pursue effective foreign policy due to internal crisis: war reparations, Stalinist takeover, Rákosi’s dictatorship, strained industrialisation, and finally pressures from state bankruptcy in 1952 and political chaos after Stalin’s death led to the Imre Nagy reform government (1953–55) and ultimately ignited the 1956 uprising. After the 1956 revolution, Hungarian communists struggled to persuade Third World countries to vote against the “Hungarian question” in the United Nations due to the Western condemnation of the Soviet invasion. The Khrushchevian opening up policy finally allowed Hungary to seek both international recognition and internal political legitimation by exporting its own model of development to the Third World, and relieve dependency from both Western economic and Soviet political influence.

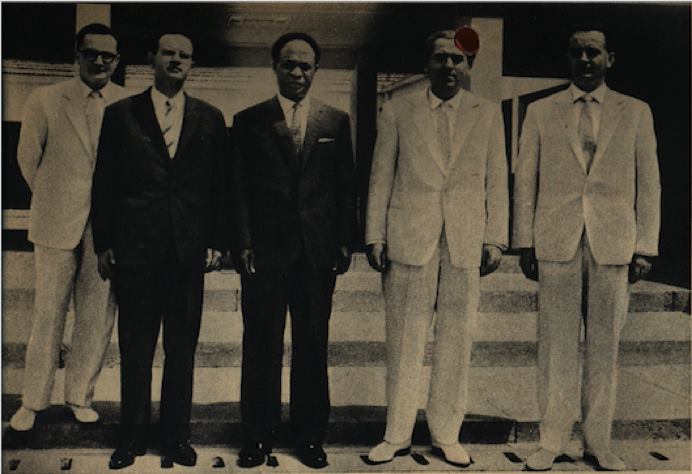

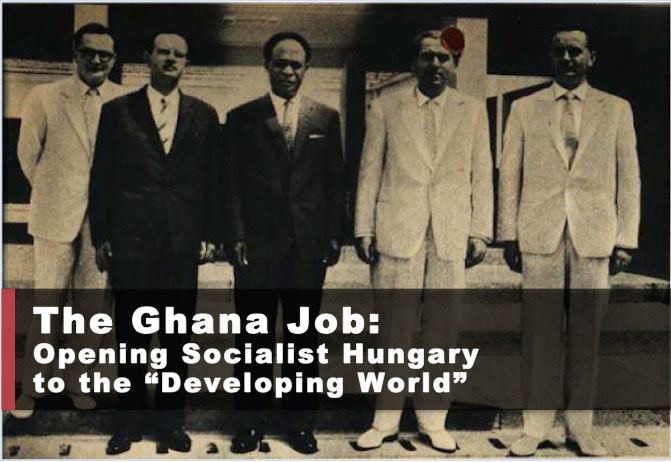

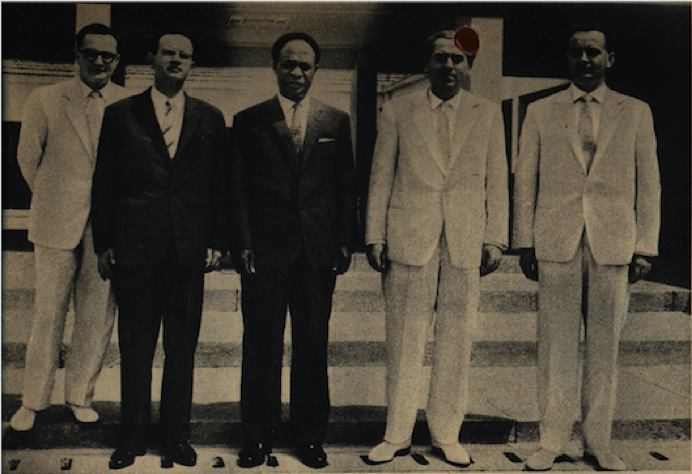

Under similar pressures, Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah looked to the socialist world to relieve Western dependency and indebtedness. After his Eastern European trip (1961), he requested the Hungarian economist József Bognár to develop the newly decolonised African country’s First Seven-Year Plan in 1962. Although having known little about African contexts, Hungarian planners could obtain a good position in offering their development and planning expertise, since they had important precedents of interwar era state-directed planning. As a result of the Ghana job, Bognár advised various other postcolonial governments in Africa and Asia, and founded the Centre for Afro-Asian Research (1963) in Budapest, which promoted export-oriented growth in order to reposition and integrate state-socialist Hungary in the global economy. Bognár introduced the concept of “poorly developed countries” to gain middle ground for experimenting with “third way” alternative development concepts between Cold War “capitalist” and “socialist” worlds, which offered the globally comparative reconceptualization of Hungarian development history and opened vistas for Hungarian development planning in the “Third World”. Bognár became a leading figure in foreign policy and the semi-capitalist reformist movement of the New Economic Mechanism (1968), into which he channeled his planning experiences from the “development laboratory” of postcolonial countries to support a mix of neoclassical economics and state-directed export-oriented growth.

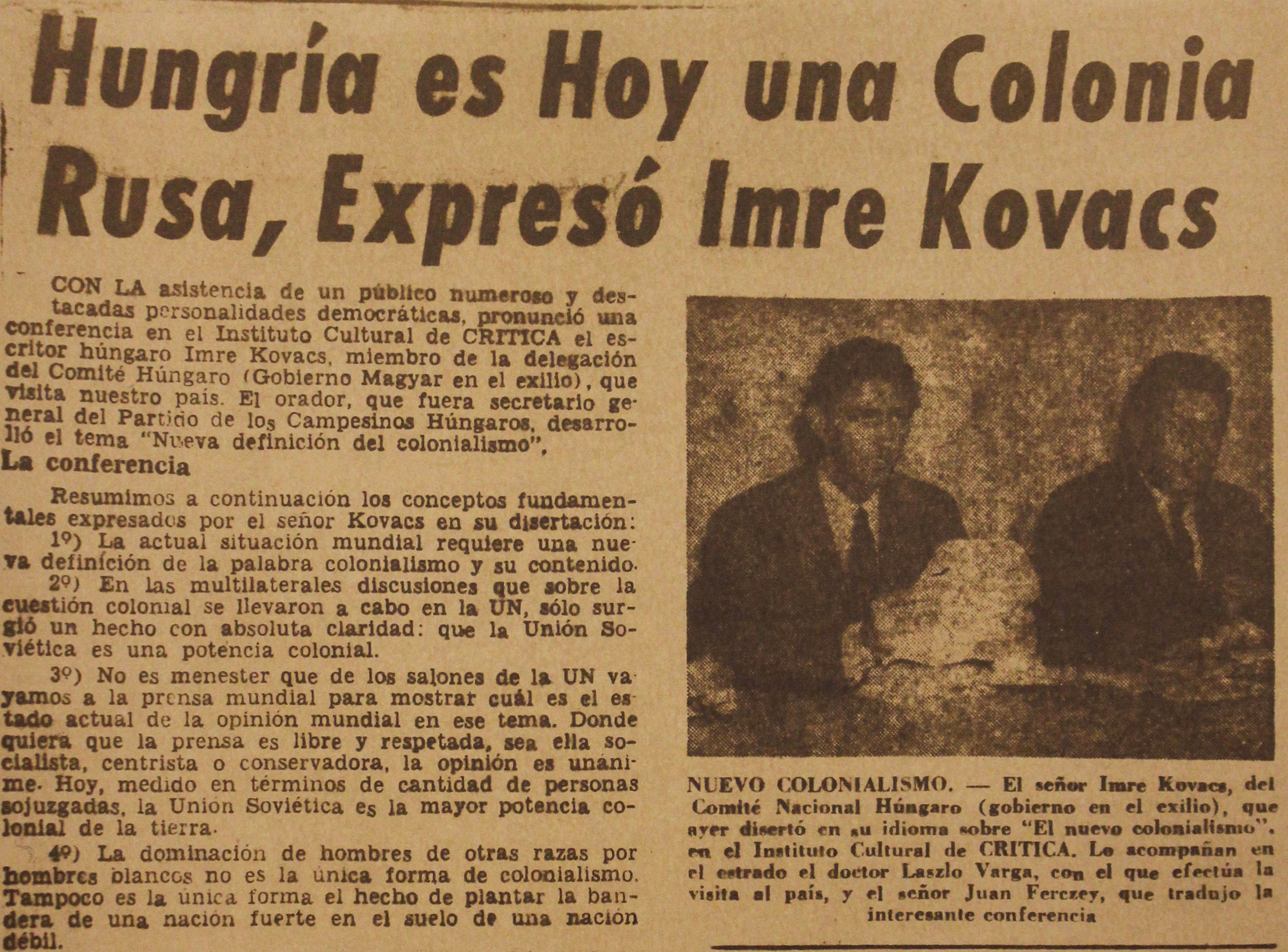

Meanwhile, Hungarian refugee experts also worked as reform advisors in Latin America, Asia and Africa in order to counter global communism with the support of the U.S. government. Nagy continued with fellow Hungarians to lobby in the International Peasant Union and use his authenticity as a symbolic leader of the Hungarian peasant movement to advise non-European postcolonial governments and share the Hungarian experience of both colonial subjugation and agrarian reform. The famous folk writer and peasant movement politician Imre Kovács was also driven by similar motives in taking an Asian trip to Jakarta, Singapore, Colombo, India, Bali, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Beirut, and then to South America, the personal and professional experiences of which he summarised in his “village research” travel diary. Kovács then used his position to covince U.S. officials to establish the International Center for Social Research in 1962, which focused on Latin American agrarian and land reform with the plan to prevent the Cuban example to spread. As he recalled,

“I argued that the perspective of Eastern European experts works better in the peculiar relations of Latin America, compared to the North Americans, and their employment would also cost less. Let us recruit refugee Hungarian, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian agronomists, economists, cultural engineers, who could after short training program acclimatize to the local context and with cooperative governments and begin agrarian reforms.”

In his diaries he drew parallels between the South American and Hungarian agrarian landscapes, rural society and interwar era socio-economic problems:

“I travelled around the continent, and everywhere I saw thirties Hungary: half-feudal society, half-dictatorial governments, large estate system, weak intelligentsia (…). The double-sidedness of politics was also the same: do reforms in a way that the old guard can stay intact.”

The colonial discourse and anti-colonial trajectories of Hungarian refugees were also taken up by the Hungarian anti-communist diaspora in Latin American, which was to strengthen after the new wave of refugees fleeing there as a result of the 1956 revolution.

The context of post-WWII global rearrangement, the crumbling of Western empires and ongoing Afro-Asian decolonisation resulted in new forms of globalising Eastern Europe. Eastern Europeans from both side of the Iron Curtain were pressured by Cold War superpowers to use their peripheral positions to gain new allies among emerging non-European postcolonies. This led to competing constructions of Hungarian postcolonial identities and positions that may be shared with the Third World. Although in ultimate conflict, both communist and anti-communist projects shared the trajectory of gathering Eastern European colonial experiences to establish common ground with the non-European postcolonial periphery, thereby trying to include Eastern Europe into the global history of colonialism. Hungarian historical experiences of peripherality and colonial subjugation, such as during the Ottomans, the Habsburgs, or the Nazis – and for anti-communists, the Soviets or Russians – were taken as exemplary cases in the global colonial ecumene, and Hungarian communists demonstrated remarkable continuities in their anti-Western rhetoric reaching back to pre-1945 era critiques regarding these matters.

The process of Afro-Asian decolonisation and the simultaneous colonisation of Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union (as proposed by many) also allowed for the globalisation of Hungarian knowledge and expertise. Hungarian refugees were forced to globalise their formerly nationalist frameworks of agricultural reforms, peasant communities and rural-garden social utopias on countering the urban/rural divide, and put these ideas into the service of solving the “peasant question” in the Third World. On the other side, communists promoted the Hungarian model of industrialisation, while experiences of interwar era agrarian underdevelopment and expertise in state-directed planning became important arguments to demonstrate that they were facing familiar problems in postcolonial countries. Both communists and anti-communists mobilised Hungary’s semiperipheral position in the global world system as a resource to gain currency in the global market of state-directed development planning. By drawing parallels between development histories of Hungary and other non-European contexts, including issues of relieving dependency and peripherality, communists and anti-communists both argued for their authentic position and unique competence in having an “Eastern European eye” to solving the great problems of the postcolonial Third World.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of my project entitled “Postcolonial Hungary” and was funded by the Socialism Goes Global project at the University of Exeter (2015–19). See: http://socialismgoesglobal.exeter.ac.uk. My project is based on empirical research in the archives of Ferenc Nagy and Imre Kovács held at Columbia University’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Special thanks goes to Professor James Mark for his outstanding help and support.

© Copyright – Content is protected by copyright!

Citation:

Ginelli Z. (2019): The Clash of Colonialisms: Hungarian Communist and Anti-Communist Decolonialism in the Third World. Critical Geographies Blog, 2019.12.23. Link: /2019/12/23/the-clash-of-colonialisms-hungarian-communist-and-anti-communist-decolonialism-in-the-third-world

Seminar Room

Seminar Room My research report to the Open Society Archives turned out to be a draft of a lengthy working paper that summarizes some of the materials I have been working with. You can read about my OSA research proposal

My research report to the Open Society Archives turned out to be a draft of a lengthy working paper that summarizes some of the materials I have been working with. You can read about my OSA research proposal

A magyar közgazdász delegáció megérkezése Accrába 1962-ben, hogy kidolgozzák Ghána hétéves tervét. Balról jobbra: Bácskai Tamás (Bognár asszisztense, egyetemi docens), Kós Péter (nagykövet), Kwame Nkrumah (a Ghánai Köztársaság elnöke), Bognár József (főtanácsadó), Székely Gábor (Bognár asszisztense, mérnökközgazdász).

A magyar közgazdász delegáció megérkezése Accrába 1962-ben, hogy kidolgozzák Ghána hétéves tervét. Balról jobbra: Bácskai Tamás (Bognár asszisztense, egyetemi docens), Kós Péter (nagykövet), Kwame Nkrumah (a Ghánai Köztársaság elnöke), Bognár József (főtanácsadó), Székely Gábor (Bognár asszisztense, mérnökközgazdász).