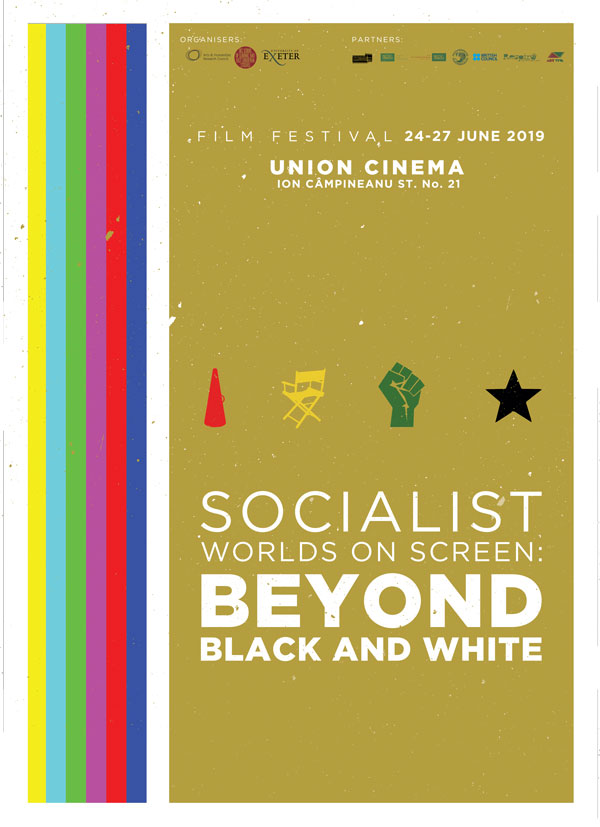

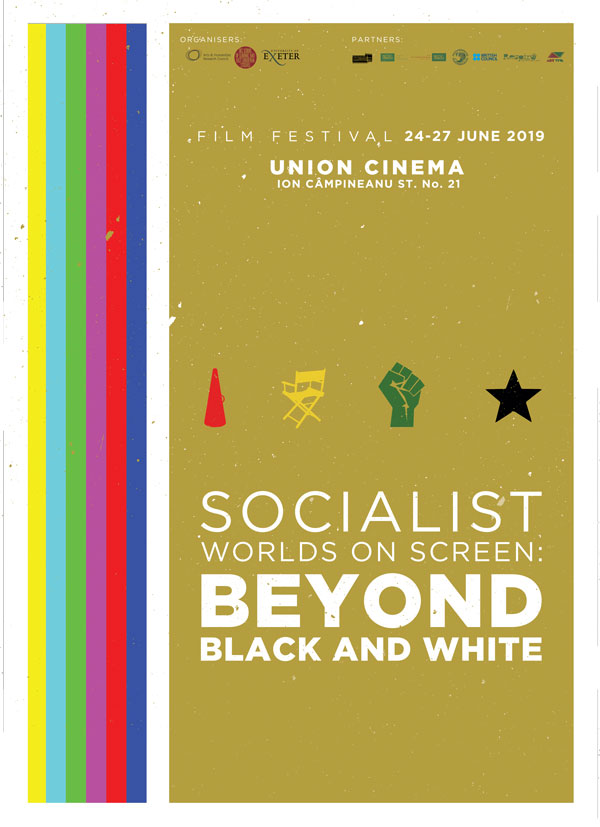

Download poster and program.

Film Festival

Cinema Union (Bucharest, 24–27 June 2019)

The history of internationalism was quickly forgotten following the fall of socialist regimes in Eastern Europe. But now these stories are surfacing once again, fascinating a new generation alive to conflicts over peoples and cultures on the move in today’s global order and seeking fresh takes on the past. This festival presents a rich and exciting range of films inspired by ideas of revolution, national liberation, and solidarity between socialist Eastern Europe and the Global South. We bring the Romanian audience stories from Cuba, Angola, Kyrgyzstan, Mauritania, and the former Yugoslavia—stories that explore belonging, border-crossing, and belief in radical change. Several of the directors featured were themselves internationalist migrants in the socialist era—men and women from the Global South who brought their talents to the socialist East. All bring visions of socialist worlds that shatter the easy black and white categories of the Cold War and raise important questions about what it means to be international, and in solidarity, then and now.

The event is organized within the project “Socialism Goes Global: Connections between the ‘Second’ and the ‘Third’ Worlds” an initiative implemented by Universities of Exeter, Oxford, Leipzig, Columbia, Belgrade, University College London and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The project is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (UK). The curator of the festival is Prof. Kristin Roth-Ey (UCL).

The festival’s partners are: the Romanian National Film Archives – Cinemateca Română, British Council, French Institute (Bucharest), La Cinémathèque Afrique, Russian Centre for Science and Culture, Embassy of Cuba in Bucharest, ‘Respiro’- Human Rights Research Centre and Association ArtViva.

The films will be subtitled in Romanian and English or French.

Each film will be introduced before the screening by a special guest.

All films will be screened at Cinema Union (Ion Câmpineanu street, no 21, Bucharest, Romania). For tickets: kompostor.ro or the ticket booths at cinemas Union and Eforie.

Monday, June 24

18.30

The Teacher (El Brigadista) – Cuba, 1978, 111 minutes, subtitles in Romanian and English, feature film.

Director: Octavio Cortázar

Introduction (10 mins) by Vladimir Smith Mesa (UCL).

The film presents the literacy campaign in the early days of the Cuban revolution (1961) in order to explore the socialist “civilising mission” of the new regime in rural regions. The conflict between past and present holds centre stage along with the impact of the new regime on the social and gender identities of the main characters. The director, Octavio Cortázar studied film at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU).

The film received the Silver Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival and the director was nominated for the Golden Bear (1978).

20.40

The First Teacher (Pervyy uchitel) – Russia, 1965, 102 minutes, subtitles in Romanian and English, feature film.

Director: Andrei Konchalovsky.

Introduction (10 mins) by Kristin Roth-Ey (UCL).

The first movie by director Andrei Konchalovsky based on a novel by Chingiz Aitmatov, who also wrote the screenplay. It presents the literacy campaign in Kyrgyzstan, focusing on the clash between generations and the conflicting identities (religious, gender, political etc.) triggered by the cultural-political offensive of the Soviet regime in the region.

Best director at Jussi Awards (Finland, 1973); nomination for the Golden Lion and Cupa Vopli (best actress) at the Venice Film Festival (1966).

Tuesday June 25

20.00

Guardian of the Frontier (Varuh meje) – Slovenia-Germany, 2002, 100 minutes, subtitles in Romanian and English, full feature.

Director: Maia Weiss.

Introduction (10 mins) by Catherine Baker (University of Hull).

The story of a canoeing trip by three students on the river Kolpa that separates Slovenia and Croatia and the conflict between their values determined by alternative views of society and tradition (e.g., gay identity) and the conservatism of local nationalist politician. The film focuses on the fluid identities and the new symbolic and physical frontiers of post-socialism – the fate of Chinese migrants in Eastern Europe is an important theme.

The Manfred Salzgeber Award at the International Film Festival in Berlin; the best actress and best director awards at the Slovene Film Festival; nomination for the director in the category “European Discovery” at the European Film Awards (2002).

Wednesday, June 26

20.00

October – 1992, Mauritania, 38 minutes, black and white, subtitles in Romanian and French, short film.

The second film by director Adberrahmane Sissako (well-known for works such as Bamako and Timbuktu) presents the love story of Idrissa, an African student in Moscow, and Ira (a young Russian woman). Their drama fleshes out the everyday challenges of human and revolutionary solidarities between the Soviet Union and African countries. Between 1983 and 1989, Adberrahmane Sissako studied at the All-Union State Film Institute in Moscow.

Nominated for the category “Un certain regard” at the Cannes Film Festival (1993); the best short film at the International Film Festival in Amiens (1994).

20.55

Rostov-Luanda – 1997, Mauritania, 60 minutes, subtitles in Romanian and French, documentary.

Director Adberrahmane Sissako and a former fighter in the Angolan national liberation war, whom he originally met in 1980 in Rostov-on-Don, embark on a journey across Angola and Benin, sixteen years later, searching for a former friend from their student years in the Soviet Union. The film analyses revolutionary hope and its disillusion from the post-independence period in Africa as well as the individual destinies of those caught in the maelstrom of history.

Special mention at the Festival of French-Speaking Film in Namur (Belgium), 1998.

Both films will be introduced (15 mins) by Kristin Roth-Ey (UCL).

Thursday, June 27

19.00

Monangambé – 1969, Algeria-Angola, 18 minutes, subtitles in Romanian and English, black and white, short film.

Director: Sarah Maldoror.

Introduction (5 mins) by Iolanda Vasile (University of Coimbra)

The title of the film is the cry of terror uttered by Angolan peasants upon finding out that Portuguese slave traders were near. It was re-appropriated as a rallying call by the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola fighting against Portuguese colonial rule. The short film tells everyday stories of the anti-colonial struggle. It is the first film by director Sarah Maldoror, who studied at the All-Union State Film Institute in Moscow and is widely considered the matriarch of African cinema.

Screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1971.

19.50

Cuba, An African Odyssey – 2007 – France-UK, 118 minutes, subtitles in Romanian and English, documentary.

Director – Jihan El Tahri.

Introduction (10 mins) by Kristin Roth-Ey (UCL).

The documentary, sponsored by Arte and BBC Films, presents the story of the Cuban military assistance to national liberation movements in Africa from the 1960s to the end of the Cold War. The film shows the central role played by Cuba in Africa’s decolonisation and in wars such as those in Angola and Ethiopia, emphasizing the fusion between socialism, anti-imperialism, and nationalism.

Awards: Vues d’Afrique de Montréal and FESPACO (2007); Sunny Side of the Docs, Marseilles (2006).