Online workshop on 10 September

Organisers:

Romina Istratii – School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

Márton Demeter – National University of Public Service, Hungary

Zoltán Ginelli – Universität Leipzig, Leibniz ScienceCampus “Eastern Europe – Gobal Area” Research Fellow

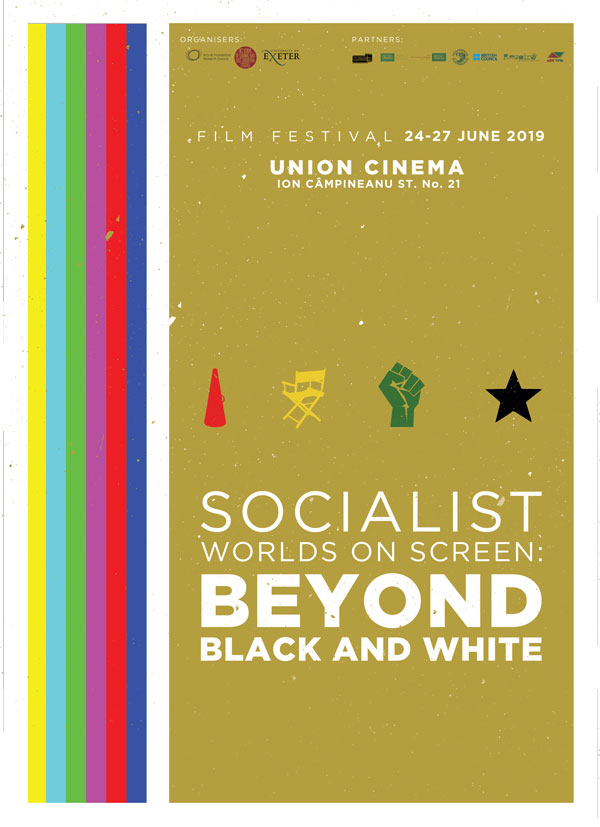

The recent events unfolding in the United States have called the world’s attention to the intersection of systemic racism and colonial legacies. Recent anti-racist protests sparked by the Black Lives Matter movement in North America and various decolonial movements in the West have significantly expanded into wider debates about colonial legacies in European societies and for first time in Eastern Europe. Voices have joined from various other parts of the world not only to express solidarity, but also to raise similar concerns in their own territories, including from Eastern European countries that did not have a shared historical account of partaking in modern colonialism. This outcome is both problematic and hopeful: it is problematic because western histories, politics and discourses continue to frame public debates around the world regardless of context-specific histories, effectively maintaining Anglo-American epistemological hegemony in the world; it is hopeful because issues of racism, exclusion or ‘othering’ may generate beneficial self-reflective discussions within every country and among every people.

These recent events demonstrate not only the continuation of western dominance in public debates worldwide, but also the need for a more organised or vocalised engagement from Eastern European scholars with colonialism, post-colonial theory and decolonial critiques. Efforts to contextualise Eastern European histories of colonisation and decolonisation in relation to Western European colonialism are not new and there is emerging scholarship in this field. Yet it appears to have only little influence on mainstream post-colonial, decolonial and ‘whiteness’ studies that currently shape discourses in the West and in many parts of the post-colonial Global South.

Calls to decolonise minds, ontologies, epistemologies and axiologies critiquing what is perceived as Eurocentric knowledge or Euro-American epistemology often suggest a uniform imaginary about European histories and epistemologies. This would be inconsiderate of Eastern Europeans’ own lived experiences of various colonialisms and imperialisms, diverse positioning vis-à-vis Western European colonialism within these countries, and in some cases direct contributions to global anti-colonial struggles. The tendencies in some “epistemologies of the South” to remain locked in an essentially Western Eurocentric epistemological paradigm, which in turn ‘others’ Eastern Europe, is particularly urgent to address. There is a need for Eastern Europeans to develop more nuanced and actor-focused accounts of their region’s complex historical experiences with modern colonialism and contemporary participation in anti-colonial struggles, in order to enter into conversation with their Global South counterparts and develop more refined theoretical frameworks together.

This epistemological ‘othering’ of Eastern Europe should not be seen as disconnected from the realities of a global scholarly landscape that remains defined by western ‘academic imperialism’: research funding inequalities, Anglophone publishing hegemonies and research standards grounded in western epistemology.

Scientometric analyses show that scholarship in the social sciences and humanities (SSH) from what is called Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) remains extremely under-represented in European and global research. In fact, Eastern Europe belongs within the Global South group in terms of its share of publications in the world. Research papers submitted from scientific institutions in CEE are seldom published in leading, high-impact international journals. In some cases, their contribution is under 1 percent, while Western European scholars’ share can be above 50 percent. Editorial boards in leading international journals tend to be comprised of western scholars and are rarely based in the CEE region; hence papers submitted to high-ranking journals are most likely to be reviewed by western scholars and not CEE scholars, which results in biases in academic peer review. In parallel, the distribution of European research grants has been noticeably uneven in recent decades: evidence shows that ERC funding on the three levels starting grants, consolidator grants and advanced grants is predominantly allocated to Western European institutions (98 percent) with their counterparts in CEE receiving less than 2 percent. More importantly, the acceptance rate of project proposals is over 15 percent in the case of Western European institutions and under 5 percent for CEE institutions.

These huge structural, material and normative inequalities in academic knowledge production suggest clear links between CEE’s limited representation in both influential publications and research funding and the dominance of western epistemology in current debates and mainstream conceptions of the world and world problems. They may also lead us to ask whether these are symptoms of wider, long-term hegemonic and dependency structures in the region that may resemble (post)colonial processes shared by other regions in the world.

In this workshop, we would like to invite scholars of Eastern European and Global or Transregional Studies from various fields to join us to explore these issues, with the aim of formulating a common strategy and organised effort for scholars in/from Eastern Europe to respond to these issues more systematically. Questions that we would like to explore include (but are not limited to):

- How can we historicise colonialism through different agencies in Eastern Europe, and how can the experiences of imperialism in the region inform global decolonisation debates?

- How can Eastern European scholars respond to the material and epistemological barriers that govern knowledge production and publishing currently?

- How can Eastern European scholars diversify and challenge constructs, theories and paradigms that remain rigidly informed by experiences of colonialism and racism in Western Europe and North America, including ‘whiteness’ debates?

The workshop’s aim is to understand better what particular historical accounts and existing representations in western scholarship Eastern European scholars might need to ‘reclaim’ and how this could be pursued collectively. The workshop will result in a short commentary that will outline the state of Eastern European debates and opinions around these questions and will identify specific suggestions towards a more organised approach in engaging with and contributing to the relevant debates worldwide.

The workshop is planned as a series of virtual discussions organised around the questions outlined above. The facilitators will open each session with a presentation to outline the state of debates and evidence around each question to spark discussion. Participants will be invited to prepare 10-minute responses to each question to contribute to the conversations and brainstorming sessions. The workshop will conclude with a round-table to summarise the key insights and lessons from the different discussions, with the aim to start drafting a statement that will serve as a future roadmap for Eastern European scholars working in Global Colonisation Debates and Decolonial Struggles.

The workshop is supported by Decolonial Subversions and the Leibniz ScienceCampus “Eastern Europe – Global Area” (EEGA) program, and aims to build on previous initiatives organised by EEGA and the Dialoguing Posts Network.

Confirmed participants:

| Rossen Djagalov |

| Kasia Narkowicz |

| Zsuzsa Gille |

| Paul Stubbs |

| Piro Rexhepi |

| Manuela Boatcă |

| James Mark |

| Mariya Ivancheva |

| Tamás Scheibner |

| Janos Tóth |

| Nikolay Karkov |

| Tsvetelina Hristova |

| Katarina Kusić |

| Anikó Imre |

| Alena Rettová |

| Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu |

| Kasia Narkowicz |

| Zhivka Valiavicharska |

| Lela Rekhviashvili |

| Vanessa Ohlraun |

| Jan Michalko |

| Denny Pencheva |

| Alena Rettová |

| Hana Cervinkova |

| Philipp Lottholz |

| Alexandra Oancă |